When it comes to Colorado Springs and the Lower Arkansas Watershed, it is as much where they take the water from as how much they take -- a three part look.

When it comes to Colorado Springs and the Lower Arkansas Watershed, it is as much where they take the water from as how much they take.

I've written a fair bit about the water in the Lower Arkansas River Valley (Southeast Colorado) and some of the problems growers down there are having as water-hungry cities like Aurora and Colorado Springs are buying up more and more water. Colorado Springs has distinguished itself in this regard lately since they've annexed more territory (needing more water), and since they've not shown any seeming interest in limiting/qualifying their takings like Aurora has.

The first link below is to a previous newsletter that would give a good overview of things if you want or need the context. The second link below goes into detail on how, even if only a few farmers sell out it can have big effects on the growers that stay.

I wanted to revisit this topic in light of ongoing conversations with growers and residents of areas like Rocky Ford and Fowler, because it turns out that there is additional detail needed to help you understand and weigh out claims like those the City of Colorado Springs is making regarding how benign their efforts are and how much they're trying to be good neighbors.

You see, when it comes to the problems that growers downstream have, it isn't entirely that their water is getting bought up and their land dried out.

It isn't entirely that a few farmers selling has the potential to harm others.**

The problem that the remaining growers are facing relates to WHERE Colorado Springs is getting their water, and how it's getting back into the watershed: that is, the Springs is taking clean water way upstream of where they bought it. Then they turn around and return dirty water to those downstream.

Water that is so dirty that it's almost to the point that crops are getting damaged.

Water that is contaminated enough with e coli that growers who grow things for human consumption (as opposed to forage for animals where the rules are looser) might soon face the ludicrous prospect of having to treat their irrigation water before putting on crops.

This is not a new problem. It is, rather, a problem that existed before, continues, and seems to be made worse as the Springs continues to pull more water out of the Arkansas to meet its ever-growing need.

To wit, consider the CPR article linked third below. The City of Colorado Springs was sued by the EPA and several counties downstream of them on Fountain Creek over the filthy water that was coming out of the city. In addition to sediment, bacteria, trash and other contaminants washing down Fountain Creek, it's a favorite spot for homeless people to camp, camps that bring the attendant questions of how sanitation is being maintained so close to a waterway.

That suit was settled (see the fourth link below) with the city having to pay a fine and clean up the creek. Colorado Springs has made progress (the CPR article dated from 2020 mentions significant improvements), but problems still remain: the homeless are still there and the water still tests over the state's limit for pathogenic bacteria such as e coli.

Parts 2 and 3 today will present the problem in summary along with some references for more reading if you are interested.

**Here I want to have some care and make sure I mention that I am not judging harshly when a farmer sells out. If you worked your whole life, and none of your children or neighbors want your land, you should have the ability to retire and enjoy some rest. You must remember that in all of the discussion of farmers selling out there are legitimate and reasonable arguments to be made about private property rights and someone getting to capitalize on their years of hard work.

https://coloradoaccountabilityproject.substack.com/p/lets-talk-water-in-the-lower-arkansas?utm_source=publication-search

https://coloradoaccountabilityproject.substack.com/p/whats-harmful-about-just-a-few-farmers?utm_source=publication-search

https://www.cpr.org/2020/07/24/after-decades-of-neglect-fountain-creek-holds-new-promise-for-colorado-springs/

https://www.epa.gov/enforcement/colorado-springs-settlement-information-sheet

Related:

The City of Thornton is taking water from high up in Larimer County in a similar way to Colorado Springs taking water from higher up on the Arkansas River. See the story below.

Why? Same reason as the Springs': it they take cleaner water from higher up, they don't have to spend as much to treat it.

Of course, that says nothing for those that get the water downstream of Thornton, but that's not really what's at stake right?

https://coloradosun.com/2024/05/09/larimer-county-thornton-water-pipeline-approval/

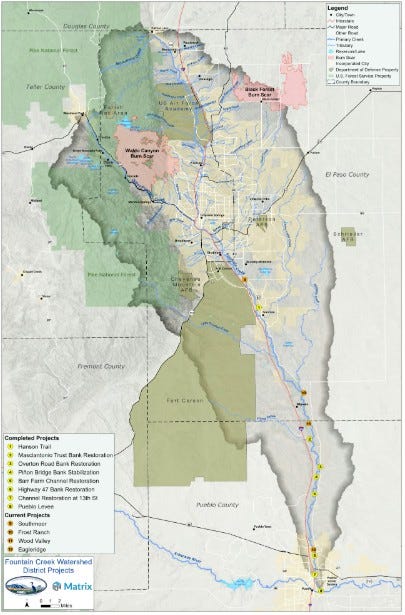

The fountain creek watershed

Colorado Springs draws its water from two primary areas. The first is out of Twin Lakes up near Buena Vista. The second is via a couple of pipelines which draw from Pueblo Reservoir.

The primary way that water makes its way back downstream from Colorado Springs is via the Fountain Creek watershed. In screenshot 1 I made a schematic diagram of how water comes up out of the Pueblo Reservoir and then returns to the Arkansas River via Fountain Creek.**

This is the water that the Springs buys up from growers in the Lower Arkansas River Valley; they buy it from people whose land is further downriver from Pueblo, but don't take it from there. They pull it out of Pueblo Reservoir.

I have heard a rumor, though cannot provide documentation, that the Springs is now looking to buy YET MORE Arkansas River water from growers further downriver than places like Fowler. If that comes to pass, presumably this water would also be taken from up in Pueblo Reservoir.

Why does this matter? I.e. why is it significant if the Springs takes their water from the reservoir rather than taking it from right next to the diversion for an irrigation canal near the growers? It all relates to the amount of things the water picks up as it makes its way downstream and what route it takes.

Prior to the Springs taking water from the Pueblo Reservoir, water in the Arkansas river that left the Pueblo Reservoir joined water flowing out of Fountain Creek from the Springs. The water that came out of the Pueblo Reservoir was relatively "clean", that is low in dissolved minerals, dissolved chemicals, and pathogenic things like bacteria.

Water that comes from Fountain Creek is not as clean and hasn't been historically. The creek bed in the Fountain watershed is different geologically so it's always had more dirt and minerals, and the runoff from the city has chemicals, contaminants, and pathogens in it from things like lawn fertilizer, parking lot runoff, etc.

Previously this contamination was not as big a problem because the relatively cleaner Arkansas River water diluted the relatively dirty runoff from Fountain Creek. This is an extreme example but illustrative: imagine the difference in mixing 1 gallon of water dyed red with 9 gallons of pure water vs. mixing 9 gallons of red-dyed water with 1 gallon of clean. The latter is going to be a lot redder, and it's closer to the situation that now exists.

With Colorado Springs pulling water from higher up the Arkansas River (at the Pueblo Reservoir) and running it through the city means that more of that water is shunting down Fountain Creek. That means more water scouring the bed of Fountain and picking up its minerals and silt. Silt that other contaminants can ride piggyback on. That means more water running off lawns and into storm drains carrying fertilizer. That means more water carrying waste and trash from homeless camps. That means more water carrying dissolved solids.

And it means more dirty water is mixing with less cleaner water to dilute the contaminants.

The dynamics here can get pretty complicated, pretty quickly, but to bolster my claim about more water flowing from the Springs down Fountain Creek, I attached graphs 2 through 4.

These graphs come from the USGS water data site linked first below. They are water discharge rates (how much water is flowing in the river measured in cubic feet of water passing a given point in 1 second) for Fountain Creek vs. time. I pulled a graph for 2024, 2014, and 2004 as you go from screenshot 2 up to screenshot 4.

You will see variations in the graphs and (sometimes HUGE) deviations from the average rate of flow. These spikes have been happening since there was a Fountain Creek; sometimes a big rain event will temporarily swell a river. Those deviations, therefore are not the critical detail here.

Pay attention instead to the horizontal grid line at 40 cubic feet per second. As you look, ask yourself how many times the graph has excursions above 40. If you look closely you'll see exactly what I'm talking about. From 2004 to 2014 to 2024, the "floor" is rising. The data points are more and more getting above 40, and sometimes by a lot.

That is, the base amount of water leaving Colorado Springs down Fountain Creek is going up. This extra flow cannot but carry extra things in it, extra things that wash up on the doorsteps of the growers downstream.

In the post after this we'll look at what is in that extra water that's washing down to growers.

**The water from Twin Lakes is not germane to this series of posts and is, I believe, an older existing water source that the Springs was using prior to taking water out of the Arkansas River.

https://waterdata.usgs.gov/monitoring-location/07105500/#dataTypeId=continuous-80154-0&showMedian=false&startDT=2024-01-01&endDT=2025-02-17

https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/16/10/1343

What is in the water coming down Fountain Creek and why is it a problem for growers?

Plants have to eat just like we do. They make some things on their own, but there are some nutrients necessary for plant growth (thus crop growth) that the plants need in their environment.

And, just like with us, a superabundance of things in the plant's diet can cause problems. In fact, too many nutrients can be toxic: it can be directly poisonous or it can alter soil chemistry to the point that the plants may not be able to take up the nutrients they need from the soil. Salt is an example that comes easily to mind. As with you drinking seawater and getting sick, plants need some salt but suffer if there's too much. Soil with too much phosphate, for example, binds iron and keeps the plants from getting it through their roots.

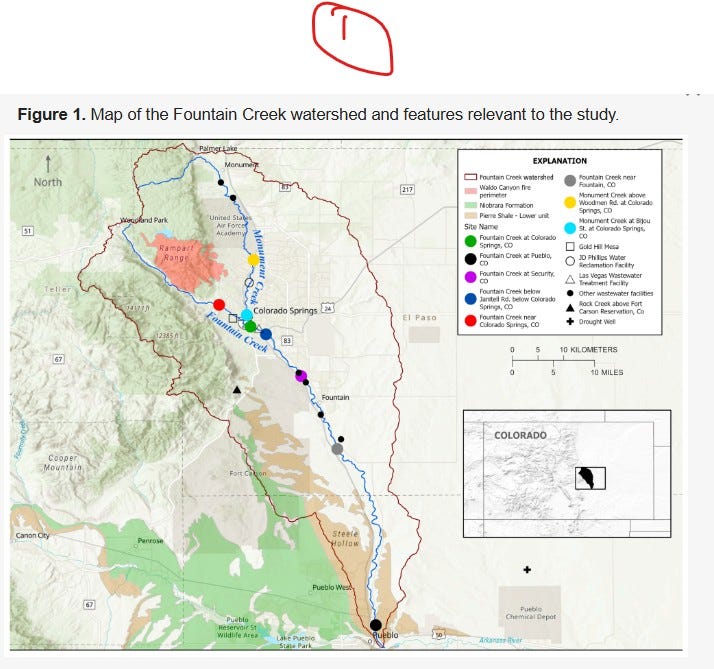

The first link below is a 2024 study done on Fountain Creek which, among other things, looked at water quality. Screenshot 1 from the study shows the location where the water was sampled at various positions along the creek. Note the position of the red (mostly upstream of the city), blue (close to right after the city), and black (down in Pueblo where Fountain Creek joins the Arkansas River) dots, this will come up later.

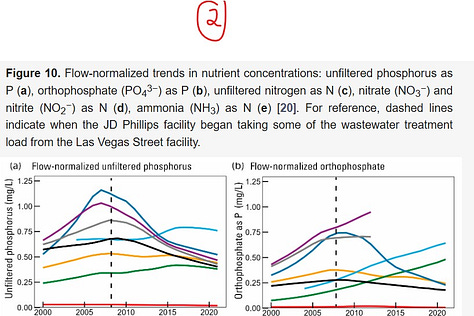

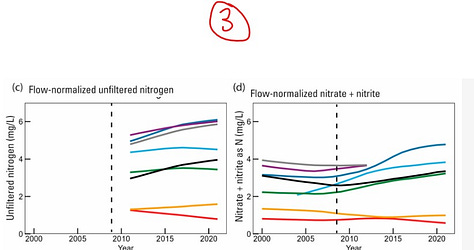

Screenshots 2 through 4 are from figure 10 in the study and they show dissolved nutrients in the water vs. time for the locations above. As a quick note, to get a decent size on the graphs I chopped Figure 10 into three pieces. The legend for the graph appears in the third, but, again, the main detail to focus on are red, blue, and black lines (before the Springs, after, and Pueblo).

There are a couple patterns that hold for most graphs (with ammonia an odd exception). Across the years of data for this study, traversing the city picks nutrients: blue is higher than red. This level seems to decay, to varying degrees, by the time Fountain Creek hits Pueblo. Also, across the years, the red line, pre-city levels, stays relatively flat.

These two patterns put together point to the following: the rise or fall of nutrient levels at any point in the creek do not seem to be coming from anything that happens PRIOR to Colorado Springs. Fountain Creek picks up a bunch of nutrients passing through the city, part of which is bound or consumed as the water continues down the creek. The levels fall, but are still higher than prior to passing through Colorado Springs.

There is some important context in the study dealing with these graphs. I took a screenshot of this discussion and attached it as screenshot 5. I feel it's also fair to note that some nutrients in Fountain have fallen with time (revisit phosphorous from screenshot 2 as an example).

Are these levels excessive or toxic? Perhaps not in and of themselves, but remember the larger context. The water here with higher nutrient levels is now starting to become more and more a share of the total river water that growers use. How much easier and how much longer til the cup runneth over?

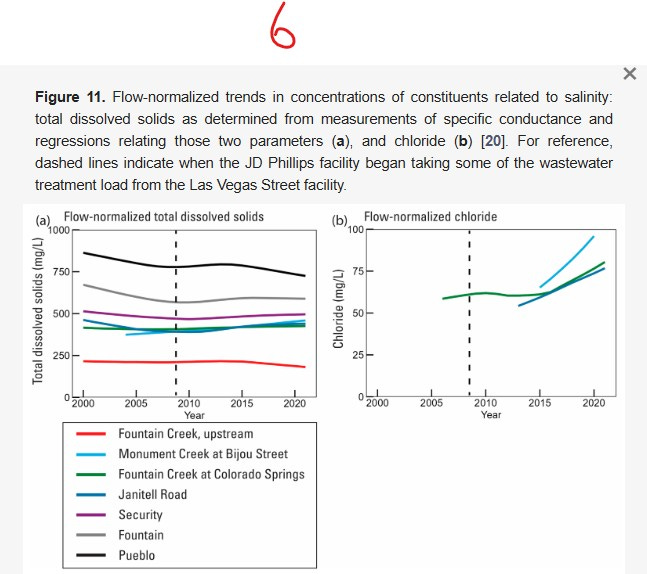

Consider now the levels of dissolved solids (TDS) in Fountain Creek. Dissolved solids are, as the name suggests, things that get dissolved into the water. Salt would be one such solid, but be aware that dissolved solids are by no means ONLY sodium chloride, there are other things in the mix, but TDS is a handy proxy for salinity.

Screenshot 6 is from Figure 11 in the study. The panel on the left is a measure of total dissolved solids vs. year for the same locations as before. You can see that Fountain Creek picked up dissolved solids in the Springs and then picked up yet more in the remaining length of Fountain Creek. Also note these graphs are also largely flat with time.

As above, you have the same questions. Perhaps no hazard prior, especially when Fountain Creek was the minority when it joined the Arkansas, as the city is increasingly sending water it pulled from high up down through Fountain Creek this saltier water is not being diluted as much. Saltier water, just as it would be for you, can harm plants (reducing yield), or kill them.

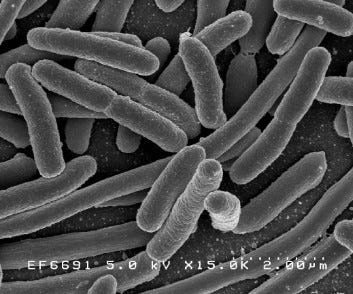

Let's look at one last thing, pathogens, organisms that may not necessarily harm plants, but which can harm those that consume plants.

The levels of the dangerous bacteria e coli in Fountain Creek has at times, including right now, exceeded the level at which the state thinks is safe for recreation or for irrigation of crops that will be consumed by humans.

I have heard various theories for the source of this high level of e coli. E coli itself is a pretty versatile little bug: it is in the digestive systems (thus the poop) of humans, cows, birds. I have heard that the high e coli levels in Fountain Creek are due to humans either as sewage effluent sent downstream or as waste from homeless settlements along the creek.

The only reference that I could find on the source of e coli in Fountain Creek is linked second below. It is a 2011 USGS study which seems to point to one large source of e coli in Fountain Creek being birds (based on DNA evidence). The authors conjectured that the waste from pigeons roosting near Fountain Creek was the main source.

Whatever the ultimate cause, however, the problem is originating in the Springs and is theirs by rights to fix.

The issue at stake for growers are State and Federal rules governing water quality. There is an upper limit on e coli contamination for any water used to irrigate human food.

Water in Fountain Creek has repeatedly spiked over this limit, e coli levels in irrigation water have spiked. If these spikes continue (or if the levels raise and stay up), anyone growing food for humans would be forced into the ludicrous and bizarre position of having to treat their water for pathogens before they could use it to water their crops!

Colorado Springs buying up water and taking it from upstream has been a double whammy to growers unfortunate enough to still want to continue to produce and who live downstream. The high levels of bacterial contamination have forced many to shift away from food for people to growing forage for animals. The high levels of salts and other nutrients have started to get to the point of injuring those crops as well. This leaves many wondering, "Now what?"

Buying up water, even when it's not the buy and dry that ruined sections of Southeastern Colorado, is not harmless. The harm it creates go beyond simply drying up land that was once productive or causing problems for the growers that stay. The where and how of the water being removed from a given river, as we saw today, can also cause problems, problems such as water that is not only unsuitable for growing food for humans, but also salty and dirty enough to injure plants.

It bears repeating that we cannot ignore the rural parts of this state, we cannot ignore the needs of Ag in this state, so that cities can grow easily without bound. Thoughtful problem solving of SHARED struggles in this state recognizes that we should seek solutions that balance the needs of everyone at the table, not the "I'll take my cut from the middle, thank you" approach we have now from Colorado Springs.

https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/16/10/1343

https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2011/3095/