That water we're putting on the ground to grow our food? Yeah, apparently that too is driving climate change. A two-parter on that, then, because it's Friday, a "lousy" theory.

Apparently irrigating crops is a greenhouse gas hazard.

And no, here I'm not referring to the evaporation of irrigation water (water is a greenhouse gas, our most prevalent in fact). We're talking here about CO2, and to a lesser extent nitrous oxides.

I want to talk about an article I saw in the Sun a bit back titled "Irrigation emits greenhouse gases. Now Colorado researchers know how much and where the top emitters are."

I want to tackle the article and the study so this will take a couple of posts. In this first one, let's talk about the themes behind research such as this. In the second, we'll look more at the research itself.

I pulled some relevant quotes by the researcher, CSU's Dr. Driscoll, from the Sun article linked below. Note: these are non-contiguous quotes and are put into screenshot 1 for space reasons.

Look in particular at the quote I highlighted. It's how the Sun reporter chose to end her article and I think it pretty well sums up the desired effect and end product of research such as this. Dr. Driscoll may not intend it this way, but over and over the same pattern has emerged.

Research like this gets used to drive policy, but not always thoughtful, balanced, or "locally relevant". This is particularly the case here in CO where it's Front Range politicians imposing policy on rural areas they probably couldn't find on a map, let alone know much about.

As a quick aside, if you're in Ag and have wondered when the greenhouse gas people will be coming for you, my guess is sooner rather than later. The Front Range will turn their gaze to you when they're done with utilities, factories, etm. If you've not yet, start paying attention and speaking up now.

I also point you to Dr. Driscoll's characterization of the recommendations in the Sun article as "low-hanging fruit". This is reflective of a common trouble for academics. They are the closest thing we moderns have to a priestly class. Many are immune to (and ignorant of) economic tradeoffs. The suggestions here are likely FAR beyond the reach of most operations. All the more so for small outfits.

If we were to try and follow through with a lot of the recommendations, this means one or more of the following:

--A huge cost for farmers/ranchers. Severe economic distress/failure for some

--Higher prices for consumers of things like, you know, food

--Lots of subsidies, i.e. higher tax burden for you and I

--Lots of talk about a need to changes things and not much actual change

Everything in life is a tradeoff. We humans do not live apart from the natural world, we are immersed in it and cannot move through space and time without leaving a mark somewhere.

I am on board with Dr. Driscoll in the sense that we should be using our reason to identify ways to do what we need to survive that minimize harm and maximize output, to identify ways to be thoughtful stewards of the planet we live on.

I think she is perhaps being fanciful and less than realistic in her expectations of what her research means, how it could be applied, and the actual constraints and tradeoffs we face in trying to feed ourselves.

In part 2, we will assess the strength of her research.

https://coloradosun.com/2024/08/05/colorado-researchers-new-data-greenhouse-gases-irrigation/

https://www.nature.com/articles/s44221-024-00283-w.epdf?sharing_token=RIrW0qc4L9iI855qPc3abdRgN0jAjWel9jnR3ZoTv0NcU-cJUpNQII-TqF7nzlOH5D8sbalCmAXHgkqon0uOY6Cp9QIPhb1uPzqhy_gvxqgnElFGm0EFcc596Xk_0lDqUQl82I8mfoTXk6ybMZHNpE7Pqu_Jo7msYcYJViKfcoA%3D

Related:

In the Sun article above, the reporter takes pains to note that the research conducted by Dr. Driscoll appeared in a peer-reviewed journal.

I can tell you from personal experience that this particularly reporter places great stock in this particular measure of research. She's reminded me of such in correspondence.

Peer review is a good start, but as you can read in my previous post on the topic, not an absolute guarantee that it's right or that it's quality.

There's more to the story.

https://open.substack.com/pub/coloradoaccountabilityproject/p/what-is-peer-review-hey-lower-south?r=15ij6n&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web

A look at the research behind the claim that irrigation is a driver of greenhouse gases.

The previous post was about the themes found in a Colorado Sun article covering some research out of CSU. This post is about the research itself.

It's not feasible for me to go into depth on the entirety of the paper. Instead what I will focus on here is in showing you another tool to add to your skeptic's toolkit when reading papers.

Specifically, let's look at the paper's claims and then something that the paper leaves out which by rights ought to be in it.

On to the paper. It's linked at bottom, titled "Hotspots of irrigation-related US greenhouse gas emissions from multiple sources". The lead author is Dr. Driscoll of CSU, who I mentioned in the previous post.

The subject of the paper's pretty easy to pick up from the abstract. It's attached as screenshot 1.

I highlighted the author's research topic in blue. One of the main themes in the paper is highlighted in green. In plainer language, you have here an estimate of how much irrigation contributes to greenhouse gas emissions,* broken down to the county level, so that policymakers could better target efforts at cutting down on emissions.

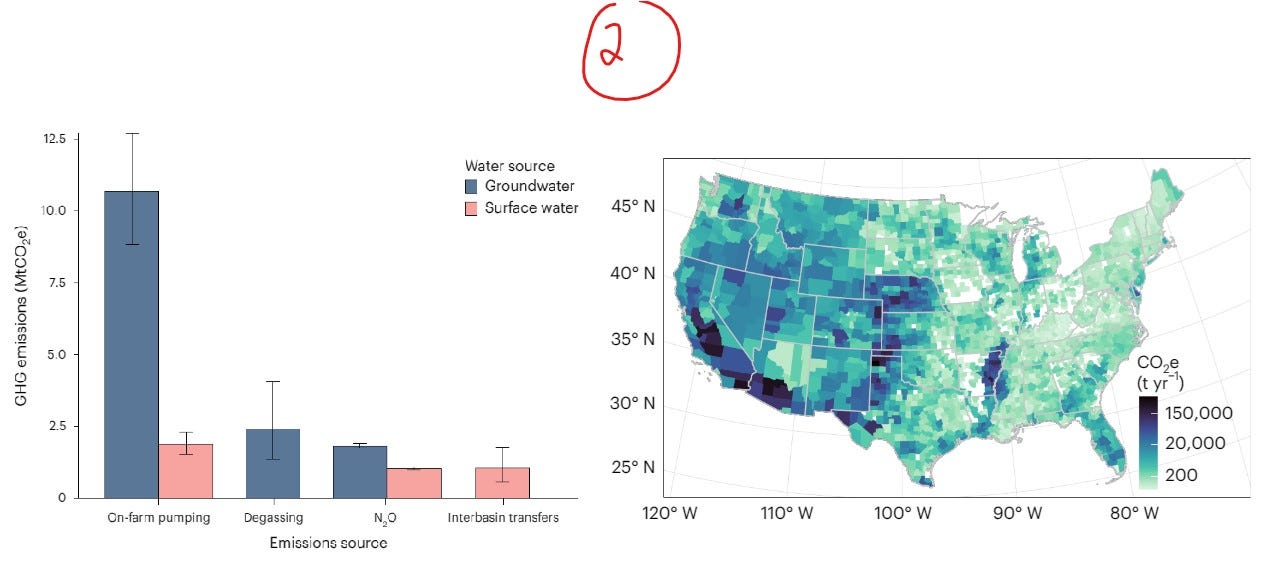

A visual summary of the results of Dr. Driscoll's research are in screenshot 2 attached. On the left is a graph of estimated greenhouse gas totals vs. source for groundwater and surface water use. On the right is a spatial (county-level) map of the US showing the estimated greenhouse gas emissions related to irrigation and water use.

Neither one is terribly surprising if you think it through. To use groundwater, you need to pull it up and move it around (compared to, for example, flood irrigation where it's all downhill in ditches). Moving water against the way it would like to flow means energy. That means emissions of some kind.

Similarly, with the exception of a lower Mississippi blip**, the emissions from irrigation are estimated to be mainly in the West. The area that relies more on irrigation than the wetter mid- and Easterly parts of the country.

In a broad sense, nothing of this is controversial. What about the details, the granular county by county data and the numbers? That's more of a grey area.

In assessing efforts like these, it's important to remember to not let the mathematical language and jargony-sophistication make you think what's being asserted is a certainty. These are estimates, and estimates are not (repeat ARE NOT) measurements. They are numbers plugged into a computer model which a computer computes according to the rules we've told it to use. When it's done, it spits out a guess.

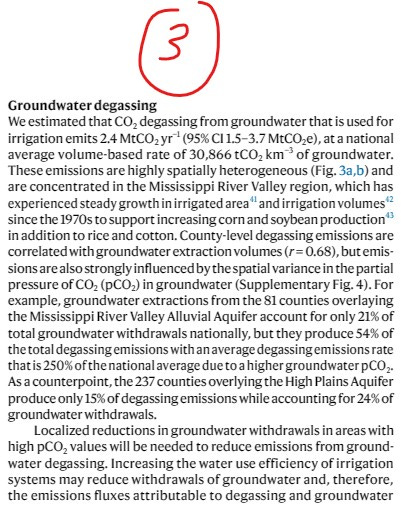

Let's talk about one of the drivers of CO2 emissions mentioned in this paper: the amount of dissolved CO2 in groundwater. Unsurprisingly, if you estimate that farms that have to pump their water up out of the ground have higher emissions due to estimating that there is more dissolved CO2 in that water, you'll calculate that farms pumping groundwater will have more emission.

I hope now you can appreciate the cartoon at the top of this post.

The chemistry is pretty simple. Next time you open a soda, you'll see similar. There is CO2 gas dissolved in the soda. When the pressure is released, it comes out of solution and escapes to the atmosphere. Same with well water. The CO2 dissolved there will, in part, be released into the atmosphere.

This effect cannot feasibly be measured for every single well, however. You must estimate. In order to save space, I copied from the paper their estimation method. Those are screenshots 3 - 5 coming from p 3 of the report.

Let's put aside the reasonable concerns about the way this was estimated and focus in on something missing here.

When you model something, when you try your best to check it, part of your due diligence ought to be to compare your modeling outputs with reality. If they match, this would seem to lend credence to your procedure. If they don't this calls into question your results and may point to a need for revision.

I looked through the paper to see if this sort of check was done and I couldn't find it. I couldn't find it for the dissolved CO2 or for their estimates of N2O (another greenhouse gas mentioned).

The closest thing I could find to a comparison is what you see in screenshot 6. The authors here compared their estimate to someone else's estimate and found it was 40% off. This paper has an estimate 1.4 times bigger in fact.

I emailed Dr. Driscoll to see if any sort of check was done on her estimates. Did they do any actual in the field measuring to see about dissolved CO2? N2O? As of this writing I've not heard but I will update if I do.

The problem here is that advocates, policymakers, and even Colorado Sun journalists do not consider these sorts of important details when they use this as a tool to justify their desires and perspectives. These lapses, the fact that it's an estimate and that no check was made as to its validity, are left out.

After all, it was in the paper and done by smart people right?

Zooming back out from this look at one particular paper, dependably-sourced, low cost food (and here you need to remember that this isn't just for things like wheat--a good deal of what's grown is animal fodder and thus affects animal proteins as well) produced in the West requires water.

Dry-land farming techniques sometimes work out here, for certain crops in certain years, but it's a gamble. Gamble means uncertain supply which means high prices.

There is no choice without consequence. If we intend to grow things here in the arid West, we must irrigate and that choice comes with a number of consequences.

Whether iirrigation drives greenhouse gas emissions is likely a settled question with the answer being "yes it does". Does it contribute more or less than other things? That is not settled and this paper doesn't (in my mind) point reliably to quantities, only to broad trends. Given this, even as a guide for state level decision making, its value is questionable.

As our planet fills with more and more people, we'll have to find ways to squeeze food out of the finite land we can reasonably put under the plow. If irrigating some lands raises CO2 levels, if (and this is not a settled question) this raising causes some harm, it may have to be something we learn to adapt to.

We gotta eat.

*Again, here I will, as I did in the previous post, differentiate between water vapor (by far and away the most common greenhouse gas) and CO2. We're not talking about evaporated water, we are talking CO2 emissions related to irrigtation.

**This blip being an area where the high estimates of dissolved CO2 mean that, even though not as much irrigation is needed, the high concentrations estimated result in high emissions.

A lousy theory ...

That time of the week again. Time for something for fun and not related to current (we're all the way back in the Stone Age today) politics.

There is likely an important point hiding in the fact that humans have more than one kind of lice that like to inhabit our bodies.

You see, most animals that get lice ... get lice. That is, they get one kind. Whether the lice inhabit their heads, their chests, their tender niblets, it's just one kind.

Humans are different. We have more than one kind of lice. Head lice, pubic lice (which I have to be honest I'm not sure whether or not these are genetically different than head lice or whether they like a more Southerly clime), and "clothing lice".

The latter, clothing lice, are distinct genetically from head lice and this is the important detail that's been right under our noses for a while.

By looking at the genes of related-but-different animals, and knowing a rough rate at which mutations occur in DNA, it's possible to get an approximate date at which the two different animals diverged from one another.

When you do this with head lice, which were around first, and clothing lice, you find that some time between 83,000 and possibly as early as 170,000 years ago (according to the paper below if you want some headier detail on this topic) the two diverged.

The obvious conclusion? Since clothing lice live in human clothing and are unique, it's a reasonable jump to say that humans started wearing clothing of some type around the same time that the clothing lice evolved.

Had you ever thought clothing was around that long?

An important caveat here is that clothing is a loose enough term to encompass things like loincloths and etc. That is, I don't think this date conforms to clothing even in the rough sense of what you picture a neanderthal wearing (and here I expose my ignorance of Stone Age chronology because I may have just committed a faux pas, depending on when Neanderthals were out and about in relation to 83K years ago).

Okay, off I go. Enjoy your Saturday and back at it Sunday.