Take a day trip to learn about rural CO. Cultivate a healthy skepticism about big change with little effort. Yet again, CO turns to Ag when we're short on water.

Fancy a day trip? Want to learn more about the rural parts of our state?

I wanted to share a day trip idea with you, especially if you live in or around the Front Range. My local museum, the Overland Trail Museum (see the FB page linked first below) will, starting 8/1 and running into mid September, be hosting a Smithsonian exhibit called "Crossroads: Change in Rural America".

It's been an exhibit I've been following and waiting to see for a while now.

I say especially if you live in or around the Front Range because coming up to see the exhibit will give you more than one chance to see rural America.

There is the exhibit of course, but it's more than that.

Wondered what a one-room schoolhouse on the Plains was like? Wonder what a tiny church was like? Wonder what a period general store looked like? Want to see the older Ag equipment that broke the sod and farmed it (and the tack that connected animal power to machine)? Wondered what people who lived on the Plains in older times wore to be wed in? These are all there too.

You can also, if you venture into Sterling proper, get a chance to see what a small(ish) town is like in modern times (or continue down the road to Akron, Merino, Illiff). I would especially recommend parking your car in the center of downtown and walking around. Even better if you come at a time when you can see inside the courthouse.

If you are like me and didn't grow up around this stuff, you'll find the experience to be eye opening. There's more out here than you'd think and the way you find out is by coming.

Take a day and give it a look.

https://www.facebook.com/OverlandTrailMuseum/

https://www.sites.si.edu/s/topic/0TO36000000aR1sGAE/crossroads-change-in-rural-america

Just like you should be skeptical about claims of big weight loss for no effort, you should be as skeptical about claims of big changes for no effort in social science.

We've all seen the ads.

Drink this (likely foul tasting) green stuff and, without any other change or effort whatsoever, you will lose weight.

If you're skeptical of claims like that, you should be. They're almost surely false.

I want to point you to claims you should be just as skeptical of, though they are not as obvious. They come to you dressed up in a lab coat and going by what some have (wrongly) termed "the science".

Just like claims of the one little effortless thing that completely changes your body composition are likely bunk, studies that show one tiny intervention, treatment or experimental condition with gigantic effects on a complicated system are just as likely bunk (though perhaps not intentional bunk like ads are--they can be the effect of overeager researchers and a less than skeptical media).

Let me illustrate with a couple related examples.

It's not as common (at least in what I see now), but for a while the buzz in pedagogy was all about fostering in students a "growth mindset". Strategies to reorient students into seeing themselves as capable of learning anything if they are willing to work instead of believing that they have certain fixed talents were all the rage at inservices. They might still be and it's just that I'm not running in those circles anymore at my inservices.

Don't get me wrong, I think a growth mindset is a good one to have and I agree wholeheartedly with the idea that by working hard anyone can improve at nearly anything. The problem was instead that simple interventions like posters on the wall and brief speeches at the start of the year were supposed to effect this complicated and individual mental transition.

This is the social science equivalent of eating that one simple green shake and losing weight with no other effort. It's also just as fanciful. Later researchers who tried to replicate the original studies about posters and motivational speeches were not able to get the same results.*

This notion of being able to shape others thoughts and actions by exposure to carefully crafted yet simple stimuli is part of a larger (and now largely debunked) bit of psychology called priming research: the right words will cause large changes in thoughts and behavior later whether the subject is aware or not. Exposing someone to words associated with being elderly makes them walk slowly and act older later (it doesn't really, but that was one of the classic studies in the field).

I've written in the past about a book titled "Nobody's Fool". The following example comes from that book as do the statistics. This is a paraphrase of the text. They go into greater depth on the failure of "priming" research as an example of what I'm writing about here. I repeat my recommendation to you about the book, but I included a link on this specific topic below if you'd like to learn more without the book.

Priming researchers had subjects unscramble a list of words into a cogent sentence. Half the subjects were given a sentence that could only be unscrambled into a hostile message while the others were given neutral sentences. Both groups later read a story and were asked to rate the actions of the main character as to the character's hostility.

The people given the hostile sentences (vs. neutral sentences) later rated the character's actions as more hostile in the original study. Their ratings were on average 3 points higher in hostility (on a 0 to 10 scale) than the neutral sentence folks.

Later researchers, however, noted that when put on the same statistical scale for comparison the hostility rankings were twice as big an effect as such obvious differences as the heights of men and women or the number of years older and younger people expect to work before retiring!**

If your eyebrow is raised, you're not alone. The pattern is evident and exactly as I have it above: a tiny change leads to a giant effect later. We all know this is not how the world works.

The real world is complicated. Human beings are complicated. There are multiple variables which not only affect the end result, but they affect each other as they are affecting the final result.

The idea that a tiny change in one of the (possible) variables will cause a giant swing in the end result should be taken with a healthy dose of salt, and should not be taken seriously until replicated multiple times by independent groups.

Now that you know it can happen, and even Nobel laureates can be taken in per the link below, be watchful. Regardless of the field, regardless of the topic, when you see social science or medical studies that promise a big change for little effort, dig in a little. Is this one study or are there multiple studies all showing the same by independent groups? In a rough way, not involving complicated statistics, how big an effect is this relative to other, better known results?

*A fundamental tenet in science is replicability. If you cannot replicate another's results following their same protocol, it throws their results into, well, doubt to put it diplomatically.

**Oh, and here again, the results were not really replicable as were almost none of the fantastical claims made by early priming researchers.

We owe Kansas water and, in a not-at-all surprising turn of events, we will turn to Ag to get it by retiring wells.

I've written before about interstate compacts (here synonymous with "contract" in common usage) for water. Since we are the headwaters for a lot of rivers through the dry West, we have agreements with downstream states as to water. We are required to send a certain amount of water downstream to satisfy the compacts we have with other states.

Right now, everyone, those downstream states included, are in need of water.

Thing is, what do you do about this when you're at the (God we can all hope) tail end of an extended drought?

What do you do about this when more and more and more houses with need for water are being built along the Front Range?

Who do you take from?

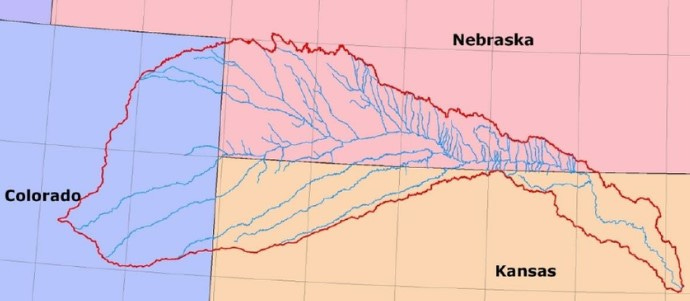

The Sun article below details a meeting had between people and Senators from both Colorado and Kansas regarding the Republican River Compact (see the attached picture for a schematic drawing of the Republican River Basin, the area of all the states that drains into that river). Worth a look and I'm glad discussions are happening; I'm glad the people involved in agriculture on both sides of the border are getting in the same room.

The background here is that Kansas, by insisting on its water via the compact, forced Colorado into a decision. Colorado's decision was to retire 25000 acres of land from irrigation (see the second link below for context). 10,000 acres need to be dried by this year and the full 25K by 2029.

Why is this the default method for dealing with shortages? Didn't have to be this way. In reading articles on this topic I keep coming across this sense of finality, but I keep also hearing that voice in the back of my mind that asks the simple question "why?".

Why is it, when someone needs to get the short end of the stick, that agriculture gets it? Always the tail end for them--behind housing and, I've heard, even things like wildlife conservation.

Pardon me, but I believe the fair way to deal with problems is to share the suffering. If it's something we have all had a part in, the solution and the pain are something we should all be sharing.

Unfortunately, that's not something reporters are asking policymakers in the capitol.

https://coloradosun.com/2024/06/27/colorado-kansas-senators-convene-amid-lingering-water-tensions/

Related:

If you look at this article, you'll know right off where the picture at the head of this post came from.

This is an older article (2015), but still relevant: a story of how you can make money in the short term and have long term costs.

https://www.coloradoindependent.com/2015/07/09/buying-and-drying-water-lessons-from-crowley-county/