Rabid enviros (and the CO Dems who cater to them) want nothing BUT electrification. So, we'll use heat heat pumps? Learn about ground source heat pumps, you'll be helping fund them.

When it comes to heating and cooking with natural gas, nothing but "tear it out and electrify!" will satisfy rabid environmentalists and the state legislators that cater to them.

Due to state laws, any utility that supplies natural gas, must have a program on file to reduce greenhouse gas emissions** by 22% of its 2015 emissions by 2030.

Xcel's original plan to do so included buying carbon credits (what I have termed in the past "climate indulgences"--I will pay someone else to plant a tree or not emit carbon so I can emit it) and using certified natural gas (this one's a new one to me--it's natural gas produced with a minimum of leaks and other environmental damage).

But rabid environmentalists leaned on regulators (the Public Utilities Commission--the Democrats' favorite non elected errand boy) to make Xcel do it without these sorts of "cuts". Xcel later withdrew the proposal to limit their emissions with carbon credits and/or certified natural gas.

See the link below for more details.

Another example of an "all or nothing" approach characteristic of the rabid environmental groups in this state and the Democrat lawmakers that cater to them.

What we're after here is not ways to reduce emissions after all. What we're after is eliminating natural gas and forcing people to electrify. Feasible or no. Cost-prohibitive or no.

It will be interesting to watch what happens in this state when reality and prices start to pinch even those that tentatively support these kinds of policies.

Will we continue on this path letting prices get higher until only those that can afford it (and those that can't afford to move) live here?

Will the ante get high enough that future Assembly's reconsider this kind of foolish policy?

Or, will we quietly do what Xcel wants to do here (buying climate indulgences and the like), rabid activists mouth-foaming be damned, so that we can meet the letter of the law, allow blowhard politicians like Polis the chance to brag, and still eat our cake instead of merely having it?

Of the three, I think it's going to be the latter. That's how things like this usually go.

Regardless of what actually happens, let me end with another prediction, this time using a quote from the story.

"Customers will cover the cost of any final plan through a new charge on their monthly utility bills."

Yeah.

**Note here that natural gas itself, methane, is also a greenhouse gas. In fact, it's more "reflective" than CO2 and thus more "powerful" as a greenhouse gas.

https://www.cpr.org/2023/11/17/xcel-wont-use-carbon-offsets-certified-natural-gas-to-clean-gas-system/

One replacement candidate is heat pumps, but they come in two flavors. Get yourself educated one kind, ground source (geothermal) heat pumps.

I have heard a lot of noise lately about geothermal electrical heat generation and geothermal heat pumps. I've written about the former, see the archives if you're curious. I haven't touched much on the latter, however, so I thought I would give a bit of a primer here.

Some important distinctions.

Geothermal (using the root words, "earth heat") is used for both heat pumps and power generation, although it's more apt to call them ground source heat pumps. That's the way I will refer to it from here forward: ground source heat pumps.

It is also important to distinguish here between air source and ground source heat pumps. I won't use the generic term "heat pump" in this post and will try to be careful in the future. If it's air source, I'll say it, if ground, I'll say it.

Simplifying things greatly, a heat pump is an air conditioner that can run in forward or reverse. In summer, it pulls heat out of your house and dumps it outside. In winter, it pulls heat from outside and dumps it in your house (whereas a regular AC only does the first).

The difference between an air source and ground source heat pump is what it uses as its reservoir. An air source heat pump uses the outside air as its reservoir and a ground source uses loops of pipe buried in the earth as its reservoir. They come in two basic geometries: either you bury a "horizontal" loop of pipe as in the left drawing of screenshot 1 attached, or you drill vertical holes and bury "vertical" loops as in the drawing on the right.

In either case, you circulate a fluid (usually water with some additives) in the pipes and you bury the pipes deep enough to be in a part of the earth that is relatively constant in temperature.* This fluid takes the heat from your house in summer and puts it in the earth and the fluid takes heat from the earth in winter and puts it in your house. This is opposed to an air source heat pump which gives/takes heat to the air around your house.

Right away you can see two key differences between air source and ground source heat pumps. Ground source heat pumps perform a lot more consistently across a range of summer and winter temperatures than air source heat pumps do. The ground is at a pretty consistent 50 degrees all year as opposed to efficiency losses as the air goes below 40 degrees for air source heat pumps.

Conversely, ground source heat pumps are much much more expensive than air source heat pumps. Drilling (then lining, then grouting) a bunch of deep vertical holes or moving lots of earth to below frost line is not cheap.**

Further, air is mobile. Soil is not. Air is relatively the same outside most comparable houses (think about the pressure, temp, humidity outside two houses in the same state, it's not hugely different). Soil outside two houses in the same state can vary widely: the ability to hold moisture, the way that heat propagates through it, etc.

As such, there are certain problems associated with ground source heat pumps you don't find with air source heat pumps.

Note: this brings us to an important caveat. The links I will use as references below are to a company that uses computer modeling and not actual data. The actual data on ground source heat pumps mirrors the predictions made by this company so what you'll see is a good qualitative (though perhaps not quantitative--the numbers may not match exactly but the patterns will) picture of what I'm about to relate. I chose these as references because the language was friendlier to a lay audience than other references.

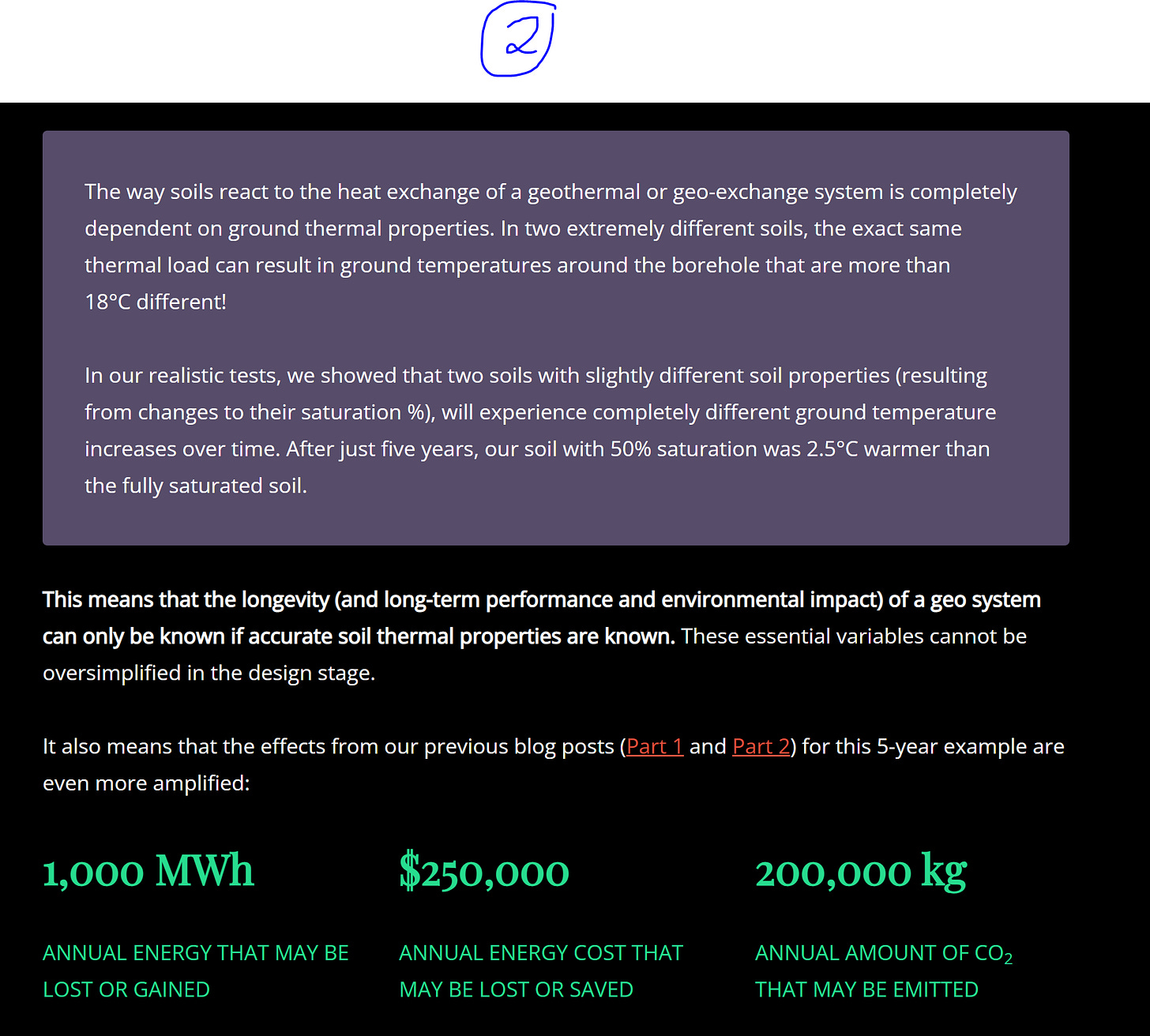

In deciding whether or not to build and/or how big to design your piping loops, designers of ground source heat pumps need to consider the soil in which the loops go. Not all soils are good for ground source heat pumps and the differences between soils that might work can be huge. See, for example, screenshot 2 from the first link below (also more detail in the first link for the motivated).

Second, depending on the conditions the building is in, you might find that the soil temperature around your piping creeps (usually up) over time. Think about it: soil doesn't get stirred by wind, it's not really mobile. If every summer you put in 100 units of energy from your air conditioning and every winter you draw out 98 for your heating, over time there's a +2 net yearly amount of energy into the soil. If the soil can't move around that heat can't move around and eventually the temperature of the ground creeps.

Again, this is based on modeling so I wouldn't trust the numbers per se, but you can trust what you see in screenshot 3 (from the first link below): a red trendline showing how the temperature of the soil climbs over time.

Why is temperature creep a problem? When the temperature of your reservoir goes up over time, for a variety of physics and engineering reasons, the machinery becomes less efficient. Screenshot 4 shows the estimates made by this company (this screenshot is from the second link below). Temperature creep can be pretty costly!

On the positive side, ground source heat pumps (like all heat pumps) do hold the promise of greater efficiency and also lower operating costs. This is because these heat pumps source the majority of their output from the earth, which costs nothing. In other words, depending on design, you could end up paying for 1 unit worth of heat in electricity to end up getting, say, 3 units of heat into your building. And because it's coming from the earth, a much more stable-temperature reservoir than the air, you can reliably depend on this efficiency regardless of the outside air temperature.

Whether or not a ground source heat pump is a good choice depends on a number of factors related to both the site, the loads, and the economics involved.

We'll dive into that a little bit in the next post.

*Usually at least below the frost line. Below that the temperature of the soil doesn't really change much year round.

**This might point to ground source heat pumps being better for big and/or multi-building uses (where you have one set of loops as the reservoir for multiple heat pumps in multiple buildings) because there would be economies of scale in the earthwork.

https://umny.ca/effect-of-ground-thermal-properties/

https://umny.ca/impact-of-ground-temperatures/

Now for where you come in: giving your tax dollars to the project.

Is a ground source heat pump worth it?

In the post previous to this one I gave a quick primer on ground source heat pumps. How they work, what some of the constraints and problems may be. What some of the positives are.

I ended that post by saying that whether or not a ground source heat pump is a good choice for heating/cooling depends on a range of factors. It depends on the kind of soil at your site. It depends on the weather at your site. It depends on the cost and how long it would to pay back.

The whole genesis of wanting to write about this topic was what you see in the first link below. Our state is taking tax money and offering it via grants to help pay for ground source heat pumps (among other things--see the link).

In order to evaluate this kind of policy, I think it's important to first have a decently solid grounding in the technology (see the post prior to this one), and then it's important to consider the economics of situation.

In other words, having learned about the technological benefits and drawbacks, we now naturally turn to questions such as "how well does this actually work when installed?" "How much does this technology cost?" "How long does this equipment take to pay for itself?"

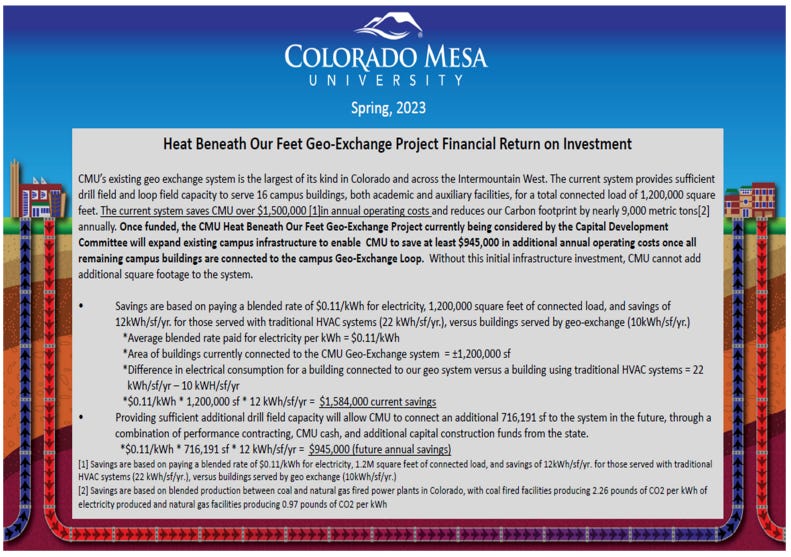

In a lot of the publicity about the new state grants, Colorado Mesa University was mentioned. I thought looking at what CMU was doing would be a good start. Their system has been in use from 2007 by what I can tell (starting with one building and then expanding with time*). For more details, see the second link below.

I sent an email to CMU to try and get some details on their system. I asked questions about the cost of the system (both to build and maintain), I asked about the soil temperatures (i.e. was there an increase in soil temperature indicating temperature creep**).

The response I got from their spokesperson was: "Our geo-exchange system has functioned with high efficiency as modeled, reflecting our assumptions that the deep earth temperatures remain unchanged."

I followed up with another series of more detailed questions. I asked for data on the temperatures and efficiency. I also repeated my questions about the costs and added one about the estimated time this system will take to pay for itself.

As of this writing my follow-ups from 11/16 have gone unanswered. My guess is that, even allowing for the Thanksgiving holiday, I will not hear. If I do I will update.

What can we make of this?

Well, first, it is possible that the system has had no temperature creep. That's not guaranteed to happen. My intuition tells me that since their system uses their Olympic size swimming pool and irrigation water as additional reservoirs they might have some flexibility and be able to watch their input/output ratio into the soil thus not heating the dirt and losing system efficiency. I would like to see more than glossy PR language to show this, but the claim is not false on its face.

Second, I would definitely like to see the numbers on the finances here. In particular, I'd like to see how much, who paid, and when the system pays for itself. In CMU's promotional materials a lot of attention is paid to how much this saves the college.

I'm sure it does. Heat pumps can indeed save money in operating costs, but it's just as important to see if they save money overall (and whether or not costs were shifted from students to, say, the general public since grants and subsidies may have funded the system so students save on tuition while we taxpayers make up the difference).

Absent hearing on this, it's hard to know. I think you can glean a little info from the size of the grants the state is offering (see the attached screenshot from the first link below): CMU would, if they were doing this today, fall under the program I outline in blue and could have up to $1.1 million of taxpayer dollars to help pay for their system.

And on top of this we have the unfilled blank when it comes to knowing how long this system will take to pay for itself. In other words, is the savings in operating costs such that you pay off the capital outlay in 5 years? 10? 30?

A lot of questions and little in the way of answers in my view and as such, I greet the promotional videos and claims I see about CMU's system with no small amount of skepticism.

Would it be worth it in other cases? I'd put it this way. If you have the money to fund the kinds of soil tests and modeling needed, would you be that concerned about the cost/payoff balance anyway? Would you be more or less concerned if you had $10,000 of state money to help you along the way?

Nah. I think this is another case where what's likely to happen is that government and large institutional customers will get things using taxpayer money that private companies wouldn't buy because they're not cost-effective, and the rich will take our tax money to help them put in systems that make them feel righteous.

*Regardless of the current state and cost of the system, something not mentioned in the promotional literature and videos when the discussion of adding buildings in and around the college is the fact that adding buildings around the campus and city to this system necessitate expanding the system or losing efficiency.

**For more on efficiency and temperature creep see the previous post.

https://energyoffice.colorado.gov/geothermal-energy-grant

https://www.coloradomesa.edu/sustainability/initiatives/geo-grid.html

A late, but related, bit of additional context:

Related:

After writing the post above, but before putting it up, I received the graphic below in (partial) response to my query asking for data about CMU's ground source heat pump.

It doesn't really address my questions posed above; I already understood the OPERATING costs were less for this system than other means of heating.

Still, out of a sense of completeness, it's attached as a screenshot.

In addition I was told that they are "...actively working on compiling the data and the updated total will be made available later next year. We look forward to sharing these insights once completed."

I will update if and when I hear.