One way to counter your truth bias. First drafts of Blue Book language are coming out. Did you sign up? You should. Force fields are not sci-fi.

A helpful tool to add to your box to counter truth bias.

Yesterday, check back in the stacks if you missed it and are curious, I posted about asking questions after reading a Sun "article" about the cost of gun violence.

I wanted to follow on that post with a quick tool I hope you find useful. This is not my idea entirely, but based on something I read recently in the book "Nobody's Fool" by Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris (see the first link below for their NPR interview about their book if you want more context). I'll probably be posting more from the book as I read more.

The basic concept boils down to this: ask yourself when someone is telling you something, selling you something, trying to convince you of something, "what's missing"?

That is, what am I not being told here?

The reason for asking yourself this simple question is a bias that we humans share. I've heard other names, but a common one is the "truth bias"--a tendency we all have to simplify our world by assuming that other people tell us the truth. A more formal definition is at the second link below.

People that want to fool you or push an agenda capitalize on this bias, and they do so in a number of ways. I'll leave it to you to read the book/NPR interview for more details, but I can share their handy tool for short circuiting your own truth bias.

It is as simple as asking yourself, "what's missing?" You're welcome to try that if you think it's more your style than a rigid system. I will share the system, though, because I like that it provides structure to those that are new at this and/or that would want it.

Imagine a friend introduced you to a fortune teller who had convinced him that they could see the future. You are skeptical and want to help your friend see that this fortune teller is more than likely a scammer before she loses money or worse.

A good framework for doing this is to lay out a 2x2 table like the one I attached as a screenshot with the fortune teller's picture in the middle.

Note how the table forces you into thinking about the things you might be tempted to gloss over. It makes you reckon with questions about how good a psychic this dude really is. It cuts through your (incorrect) intuitive notions. When is this fortune teller not right? When did they miss a prediction? What's missing?

I thought it might be handy to adapt this to a couple other areas where a reality check is sorely in order. So I made a couple more tables for your perusal and attached them: I put one for a politician and one for the media.

I will not claim to be an expert, these are just the things that occurred to me to put in a table. There are other, equally valid ways to do this and you're welcome to add your method if you'd like.

To flesh this out with an example, consider the third link below. It's a Sun article about a report that touts the success of the Basic Income Project in Denver (where cash payments, no strings attached, are doled out to certain qualifying homeless people).

I'm not against such efforts right out of the gate although I admit to misgivings. I have also (in the past) read then written about some (minor) successes that they seem to have for some. Agree or no, however, you should make a habit of asking.

I wrote the reporter and asked the following (try to note which question corresponds to which box):

Q1: How did the reporter come by this story?

Q2: Did she search out any people or information that were critical about efforts such as these? Anyone who is ambivalent?

Q3: Did she do any looking into the limits of what a self-selected study pool and self-reported data can tell us? Additionally, did she delve into the limits of the estimates provided by the researchers re. their reporting of lower costs?

Do you see what I mean? Note a couple things. One, you needn't be an expert in any field. You need only be willing to ask questions. Mine are some of a lengthy list of valid queries. Two, you may not always get an answer and that's okay. Not finding an answer ought to tell you something about the validity of what you are reading. It ought to at least make you skeptical. Skeptical means, don't trust (and don't give money!).

When someone tells you something, when you read an article, when you listen to a politician, stop and ask what's not being said. Seek out the information and/or the perspectives that are not right in front of you.

It will necessarily mean that you don't ingest as much news, but I personally would rather make sure my food is wholesome while eating less than be overfull on some dodgy stuff.

https://dictionary.apa.org/truth-bias

https://coloradosun.com/2024/06/19/homeless-payments/

P.s.

You can and should be asking yourself what is missing from this page and things I write.

That is, I encourage you to use the press square on things you see here (though I am not, and haven't ever sold myself as, a journalist).

The first round of ballot analysis language emails are hitting my inbox, I thought I'd show you what that looks like.

I posted a bit back about getting involved in the Blue Book language for this state (see the link below for how to sign up). I signed up back then and the first of the emails are just starting to hit my inbox.

If you didn't sign up and were curious for what it looked like, check out screenshots 1 and 2 from my inbox. This is not a matter for technical expertise, nor is it onerous and involved. It's looking over what someone else wrote and tossing in your two cents.

If you wondered whether or not you had time or the wherewithal to do it, wonder no more. This is something that anyone can participate in.

Speak up, add your perspective, help shape what this state looks like.

If I managed to convince you, check out the previous newsletter below. It has details on how to sign up.

https://open.substack.com/pub/coloradoaccountabilityproject/p/get-involved-with-crafting-blue-book?r=15ij6n&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web

Force fields are not sci fi. Fields are, in fact, quite a useful and extendable physics concept.

That time of the week again. This will be the last post til Sunday, and thus it's something for fun not related to politics.

I am teaching an online class (calc based physics semester two — electricity and magnetism) and the students recently passed the section on electric fields.

I know that there is a broad spectrum of interests and knowledge of physics out there, but seeing this section inspired me to take a very soft stab at sharing some physics with you. Don’t worry, this won’t be a lot of math.

Depending on where you’ve been and what you’ve seen or read, you may have come across the idea of a force field. They figure largely in sci fi, providing convenient confinement of something or another being one example.

But the idea of a force field is not science fiction.**

Let’s step back a little into history. Newton was very successful with his universal law of gravitation. It made (still makes — Newton was enough to get us to the moon) accurate predictions about almost all the gravitational phenomena we saw.

Something bothered a lot of people at the time. Perhaps it still does for some, depending on how much attention they devote to it. How on earth is it that two things can materially affect one another across completely empty space? How can a planet pull on a moon to keep it going round and round in an orbit if they’re not connected in some way by some thing?

Newton’s quote was roughly “I make no hypothesis”, fancy wording for “I dunno”/shrug. The formula worked, but a conceptual framework was lacking.

Fast forward with me a little ways to a physicist named Faraday (if you recall my earlier post about being a mechanic on an EV this name may sound familiar, the units for capacitors take his name). Faraday’s picture is at the top of the post.

Faraday is someone I mention to my students, especially those who struggle with math, because he was someone who struggled with math too. Faraday was brought up in a time where you could get an education if you had money. He didn’t.

Faraday was brilliant; he had a wonderfully fertile mind. All he lacked was a way to take his ideas and give them mathematical form. As such, he frequently thought in pictures and his mental pictures were the forerunners of the way we now conceive of the “action at a distance” that bothered scientists since Newton.

The idea (and here I take some liberties with Faraday’s ideas and other later conceptions to make the idea easier and put it in one package for those without a background in math or physics, so be gentle with me) goes like this. Empty space is not empty.

As soon as you have an object in space, an electric charge for example, all of space is filled with an electric field. Other, subsequent bodies added to this space react to this field and fill space with THEIR own field which then makes the first object react. And so on.

What may appear to be some spooky action at a distance is not one object reaching out somehow across empty space to poke another, it is objects reacting to the sum total of electric fields in the local area it inhabits. These fields are there because of the charges.

Ta Da!

I know, a minor conceptual change. Telling you how and why is hugely beyond what I can do right now, but I hope you get a tiny glimpse (and take my word for) of just how much this shift in concepts clears things up. The idea of fields in space is also quite generalizable, setting the stage for later, deeper understanding.

Calculating these fields and working with them mathematically are something we owe largely to Maxwell (another famous physicist, not pictured). Per what I wrote above, this is not where we’re headed. We’ll stick to Faraday because his conception of fields is quite good, and requires no mathematics, just pictures.

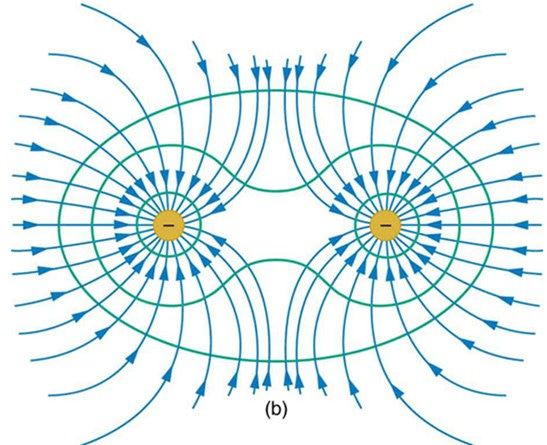

The picture with the one positive and one negative charge is an example. It shows the charges and the field lines that emanate from both. To help you understand it better, here are Faraday’s rules for drawing/interpreting such diagrams:

1. Field lines flow out of positives and in to negatives.

They cannot touch or cross.

The density of the lines gives you a sense of where the field is strongest, where an electric charge would feel a greater force.

Look at the diagram with the two charges? Can you see the outward and inward flow? Can you see where the interaction is strongest? Weakest? (If you said right between the charges for strong and on the opposite side for weak, you got it).

As soon as I drop these charges into my universe, these lines immediately fill up space and the interactions between the charges can easily be seen by the direction and density of them.

For some contrast, look at a similar diagram, but with two negatives instead of a mixed pair.

Same rules and look at the behavior now! Even if you didn’t know that opposite charges attract and likes repel, you’d get that from the pictures. Can you see how the two bundles of force lines are bunched up between them? The field lines are pushing quite hard to make sure that these two don’t get close!

Imagine their reaction if you tried to force the two negatives closer. Imagine their unfolding if you pulled the charges apart.

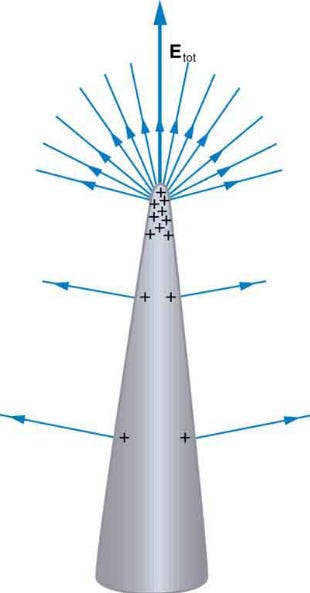

I want to end the post with one last example, because the concept of field lines is more than just a toy. It can help us understand actual physical things like: why it is that lightning rods are pointy and gothic looking?

Some is undoubtedly fanciful design, but it’s also based on the nature of electricity. Metal objects have charges that are free to move and reassemble themselves and so if you have a metal object with pointy bits (areas with what a mathematician would call a small radius of curvature) and you put it near an electrically-charged thunderhead, the charges in the metal lightning rod will collect at pointy and not blunt spots. Pointy spots allow more electric field lines to emanate from them than do blunt.

That is, the field is stronger near pointy spots because more lines can fit there without touching or crossing. See the drawing of a charged object with a blunt and pointy end for what I mean.

Since the charges can better collect at pointy spots, they become more charged and thus more attractive to a thunderhead looking to “balance its books” and get back closer to a state where its electrical charges are not separated, where it’s not so polarized.

That is, out of all the choices a thunderhead could make as to where to start flowing electric charge in a lightning bolt, it will pick the pointy lightning rod.

I hope I’ve given you a tiny hint of the flavor of a force field. If nothing else, perhaps the notion that intelligence is not always related to education and that mathematics is the language of physics, but not physics itself. The two do not have to run together all the time.

Back at it Sunday!

**This gets even more esoteric so I won’t go too far afield, but the idea of fields can be expanded in any number of ways. It’s a handy concept that generalizes well: at some point in physics (the intersection of relativity with quantum mechanics being one) the fields are not about forces anymore, they are about fundamental particles both the massive kind and the kind that mediate what we think of as forces.