Local control of education is a good thing, even if Boulder teaches things I disagree with. Part 1 of MIT's "pretty good" climate modeling.

Local control of education

You know one of the wonderful things about local control of education? People in an area get to educate their children according to their values and not those of others.

Some kids in Boulder Valley School District have been pushing the district to vote on (quoting the article below): " ...a plan for making school buildings greener, creating pathways to green jobs, and giving students lessons on climate change in a variety of subjects."

The article below has been in my queue for a bit and so I'm not sure of whether or not there has been a vote and/or its result.

I don't think I care either.

As I say above, the nice thing about a state where we have a great deal of local control in education is that the kids and parents and teachers up in Boulder are free to decide for themselves what they'd like to focus on. Just like the schools in far Southwest Colorado (see the second link about a Ute school trying to preserve the Ute language and culture). Just like schools near me.

This is how things should run. It's how I hope things stay.

I wonder if the supermajority Democrats running this state feel the same way. We've already seen a pretty big intrusion into the history and social studies curricula across this state. Will climate change education be far behind?

Will the (to borrow a phrase from the CPR article about Boulder) "Green New Deal for Schools" be forced down on everyone from the Democrats under the gold dome? The ones who know better than the rest of us how to live?

I guess we'll see.

One last interesting sidelight. While waiting my turn to testify at the AQCC meeting last week, I was reminded of the recent spate of articles about kids and climate change I've read: there were quite a few youngsters who testified at the hearing. From Boulder.

https://www.cpr.org/2023/11/28/boulder-valley-school-district-green-new-deal-climate-policies/

https://collective.coloradotrust.org/stories/on-the-ute-mountain-ute-reservation-a-new-school-aims-to-preserve-culture-language-and-sense-of-community/

MIT’s “pretty good” climate modeling.

I put the same question that the author of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists letter has at the end of his first paragraph to you: can we predict the future of our planet and its climate?

And, I would add a followup: if you think we can, how well can we predict?

This is the first of 2 in a series looking at predictions and modeling, using an MIT global model as an example.

Recently a reader shared an interview he gave with me on global warming (I link to it second below), and I wanted to share it with you. It's a bit long to cover everything in detail here, but I think it's worth watching. Regardless of where you land on climate change, it doesn't hurt to see and hear things that run counter to the common narrative.

I wanted to excerpt something out of this video and go into detail because it's something that can be generalized to other examples of modeling fairly well. That is, if you can understand the general ideas below, you can apply them to other examples where you might wonder: can we predict the future and how well?

From the video below, the part that is relevant for us starts at the 36:57 mark if you want to skip in.

If you make a model, a common way to test it is to run the model on inputs that would give you the current (measurable) conditions so you can compare the prediction against what you actually got.

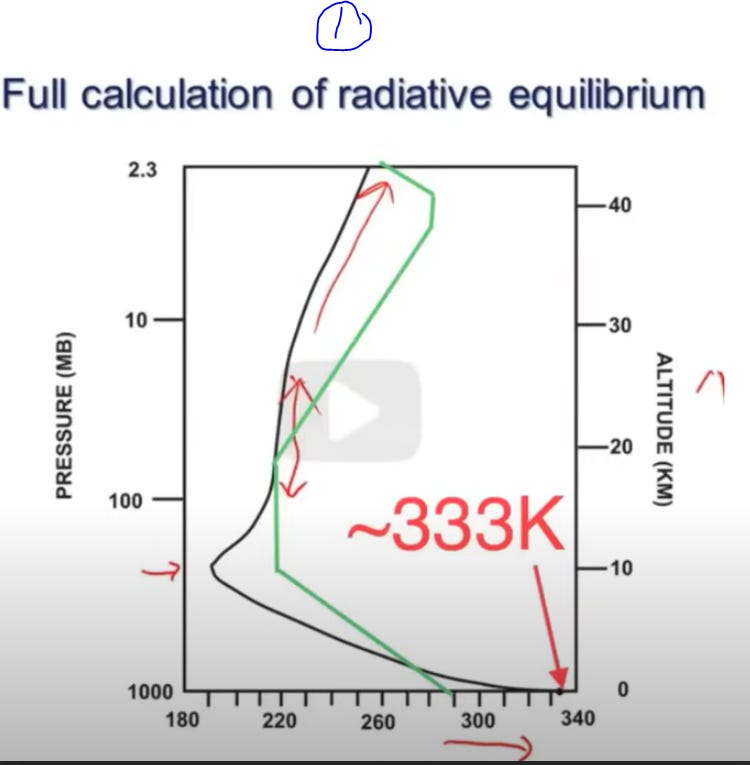

The MIT scientists built such a climate model and then compared it to current measurements. In order to make life easier on us all, I took a screenshot from the video and attached it as screenshot 1.

What you see there is a black curve that is the prediction of the temperature at various altitudes (or, equivalently, pressures because you'll note the pressure scale goes DOWN as you move up it) and a green curve that is the measured temperature vs. altitude.

Look at how much air there is between the lines, at how much distance there is between the points where the curves hit the bottom of the graph.

I think you'll agree with me when I say I wonder how it is the MIT people could say (as was told in the video, this is not a direct quote) that the two agree pretty well! Agreeing pretty well doesn't look like this to me. In fact, to give you a comparison, I pulled a random graph off the internet that shows what a much better prediction vs. actual graph would look like. That is screenshot 2.

Going deeper into numbers, the predicted vs. actual temperature in MIT's model really only seem to agree (to touch) at 20 km above sea level. Using the graph as a whole, the discrepancy between the two at any given altitude ranges from zero to 53 degrees off. That is, the model is between 0 and 19% off from reality.

A good first-pass approximation to the error in a calculated number is the error in the data (as a percent) that you used to find the calculated number. E.g. if I calculated your speed and my measurement of the time it took you to go from one spot to another was 10%, it's reasonable to think that the value of the speed I arrive at for you would also be about 10% off.

Following that rule and giving the MIT people the generosity of saying their model was 10% off, it would be reasonable to assume that any prediction about the climate that they make would be 10% off too. So, if MIT told me that the global mean surface temperature in 20 years would go up by 1 degree, I'd be pretty skeptical.

The current global mean temperature is about 59 degrees, so I wouldn't really trust any number they gave that was smaller than 10% of that or +/- 5.9 degrees. 1 degree temperature rise is, by this rule, pretty speculative and I wouldn't bet on it. It could be much more, or much less.

The same applies to any other model. In order to assess it, you need to look at how good it predicts the current state. Then you should look at how far off it is from current events (as a percent) and that gives you a good sense as to how accurately it could predict the future.

Keep this in mind when people start telling you about how solid their modeling is or how well it agrees with nature; if they can't provide you the above, they're not sharing all you'd need to be able to assess it.

One last thing. I want to end with a rather lengthy quote from the Bullet of the Atomic Scientists article below. I did it as two pieces because the two blocks of text are not contiguous in the piece.

"That geographic variation suggests that end of century global warming may be less severe than most climate models suggest. These observations do not invalidate climate modeling, but they do highlight the importance of regular comparisons between climate models and the real-world observations they aspire to reflect."

"The way that the models are both right and wrong simplifies to a math problem. A numerically infinite number of combinations bring you to the same average value. For example, two is the mean of two and two, but also the mean of one and three. In this way, global climate models are correctly arriving at the mean sea surface temperature warming, but missing the real-life regional variation. But how the ocean warms has enormous implications for global climate sensitivity, or how much the Earth as a whole will warm. In particular, because the Eastern Pacific is cooling while the Western Pacific is warming, it will yield a very different global warming outcome than if the ocean warmed more uniformly."

Hear hear. There is nothing inherently wrong with trying to model of predict. But let us all be clear about what we are getting ... and what we are not.

Let us also be supremely careful in how we use these models in making policy and/or economic decisions. The stakes and costs are too high!

https://thebulletin.org/2022/12/whats-wrong-with-these-climate-mod