Government transparency isn't that important right? Putting limits on civil asset forfeiture. What is a wetland? Who decides?

Government transparency wasn't really that important to you was it?

I linked to a couple new bills below. Both are attempts to stop/limit some aspects of government transparency.

As someone who greatly values transparency and uses CORA requests regularly, I hope to convince you of the importance of bills like this, and also the importance of speaking against them. As with TABOR, if you don't defend it, you'll wake up some day to find it gone (or neutered).

The first bill below comes with an article. Those are linked first and second below. The article is done by transparency advocates Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition (CFOIC).

I'll leave it up to you to look through the bill and the article, but I share a lot of the same concerns that are mentioned in their article.

--This bill would allow longer timelines for CORA requests than currently exist.

--This bill would allow more exceptions to CORA than already exist.

--This bill would allow public records custodians the chance to label someone as "vexatious" for their requests under certain circumstances. Such a label puts the requester on a 30 day hold. Nope. No way this'll be abused.

--Oh, and if you're in whatever the government decides is "media", you cannot be called vexatious. That's because the media are special. In fact, there are multiple provisions in this bill that the "media" can be exempted from.

--Another couple provisions that are especially galling to me are the fact that it would treat multiple separate CORA's from one requestor into one request, while greatly limiting access to employee calendars as public records. As someone working with a $0 budget, these are tools I use to direct my CORA requests and to limit expenditures. Taking these tools away is effectively driving up the costs and putting yet more things out of reach.

One last nibble before moving on to bill #2. I sent an email to the lone Republican sponsor on this bill (Soper). The email essentially asked, "what the hell man?" (but not in those words exactly). If I hear anything back, I will update.

The second bill (linked third below) applies more to the Assembly (legislators) and involves not just CORA, but the state's open meetings law. It's new enough that, as of this writing, CFOIC had no article on it. If that changes, expect an update, one that will come when I post about testifying against it.

I can't help but think that this bill is some legislators being snippy at being sued (and losing) over things like their secret quadratic voting system and violations of open meetings law: reading through the summary it carries that distinct flavor.

I have to admit that, at least to this non-lawyer's eyes, I get the distinct impression here that this bill claws back some ability for lawmakers to have meetings in private but not have to follow a legally-defined process to do so. At least, I think it's reasonable to argue that it muddies the waters here; it allows lawmakers, for lack of a more precise phrase, "plausible deniability" if challenged.

Let me show you what I mean with a quote from the bill summary:

"The bill makes several changes and clarifications concerning the application of the COML to the general assembly and its members. Specifically, the bill provides that, for purposes of applying the notice and minutes provisions under the COML, a quorum of a state public body of the general assembly must be contemporaneous."

What you have seems somewhat reasonable. Should two lawmakers talking in a hallway have to apply by every regulation of the Colorado Open Meetings Law (COML)? Indeed, I'd agree that would be excessive.

But what if one legislator short of a quorum, say a group of 4 when 5 would be a quorum, are talking. Harder to make the argument that the COML shouldn't apply here.

There are other provisions with this same savor, but I'll stop there and leave the rest to you to consider.

As of this writing, neither bill has a committee date. They are on my watchlist, however, so be watching for updates as I have them. If this topic is a passion of yours, you should add the bill links to your favorites and check back.

https://coloradofoic.org/colorado-house-bill-lets-governments-label-records-requesters-as-vexatious-take-longer-to-comply-with-requests-withhold-records-that-invade-privacy/

https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/hb24-1296

https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/sb24-157

Putting (more) limits on civil forfeiture in Colorado.

How many things that you passionately believed in as a teen do you still hold on to? Probably your list is pretty short like mine.

One thing that is still on my list is the government taking your property without due process and that is exactly how I see civil forfeiture laws.

I put a link to an FAQ page on civil forfeiture first below if you would like more context (this page found via a link in Ari Armstrong's op ed linked second below).

The short version is pretty straightforward, however. The modern version of civil forfeiture (the taking of property by the government when they suspect a crime was involved but there is no criminal conviction) is largely a result of the War on Drugs.

In an effort to make it harder to traffic in drugs, legislators expanded what had previously been a pretty narrow window of cases where the government could take property without conviction.

As you might imagine, the fact that there was money to be had quickly lead to expansion and abuse. This was only helped by the fact that the federal government shares some of its take with local governments, and, as mentioned in the op ed and the FAQ site, the feds have neatly skirted state-level attempts to slow or stop civil forfeiture abuses by "deputizing" local officials into federal service.

Colorado has made some efforts to proscribe civil forfeiture (not enough in my view, but not zero). Mr. Armstrong covers the details in his op-ed which I'll leave to you to read up on.

I would like to mention another effort in this year's Assembly session that tightens down more on civil forfeiture. It's linked third below if you this is a passion and you want to read up on it/advocate.

It's hard to make the argument that we should be concerned about the rights of drug dealers, but I would like to remind you that laws are never as surgical as people would like to believe. Whether intended or no, the government does harm innocent people and it's a hell of a lot easier to do that when you have faulty laws on the books. Civil forfeiture is one such case and we should be working to eliminate or at least limit it.

https://ij.org/issues/private-property/civil-forfeiture/frequently-asked-questions-about-civil-forfeiture/

https://pagetwo.completecolorado.com/2024/02/06/armstrong-asset-forfeiture-bill-government-theft/

https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/hb24-1023

What is a wetland and who decides? A bigger issue than you'd think.

Let me start with the background.

There is a huge amount of context here to follow up on if you're not familiar with the topic (and I wouldn't just go by the characterization of Ms.Jerd in the Water Education article linked first below).

If you want or need to study up, I recommend a Google search on the legal case mentioned, "Sackett v. EPA". That should give you enough information, plus some sense of what people on both sides of the issue think.

For my part, this is what I would say.

--The SCOTUS decision on the issue helps (but likely hasn't finished) the definition of the legal term "waters of the United Sates". This is important because anything labeled by that designation can be protected under law.

--People that like the decision see it as a step away from unelected boards making too many decisions.

--People that don't like the decision see it as lessening protections for some ecosystems, wetlands in particular.

--Probably because I'm in the former group and not the latter, I see this decision as kicking back how to define and protect wetlands to the people, and I think that a lot of the heartburn over it is due to environmentalists losing yet another arrow in their quiver: it'll be harder to pursue their agenda when they don't have the ability to block/tie up things in the courts for years.

--At the same time, I'm not looking to pave over the state or have no restrictions on development in or around wetlands.** I, like other reasonable people, want a balance between the environment and economic activity (and the ability of a landowner to do with his or her property as he or she sees fit).

In other words, I don't object to the SCOTUS decision on its face, I am just concerned about who decides.

And I'm kind of wondering, having read the article below, whether what will happen here in Colorado is that we'll simply replace environmentalist-dominated federal policy with environmentalist-dominated state policy. That is, are we going to have policy about wetlands that was as strict, or perhaps stricter, than it was here in Colorado?

The Democrats running this state have shown no compunctions about bending over backwards to satisfy their raid environmentalist constituents.

There is a Republican sponsored bill in the works (linked second below). It's not perfect, but it might offer a little bit more balance than what progressives/environmentalists are thinking. For example it moves the decision away from CDPHE to the Department of Natural Resources.

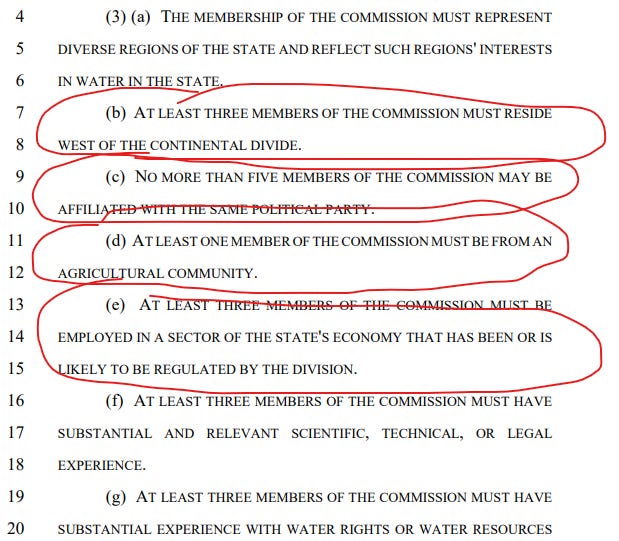

It also ensures a diversity of voices on the commission that decides. See the screenshot from the bill for examples of what I mean.

I guess we'll see. Given the tradition of the Democrats talking about bipartisanship but not actually following through, I don't hold high hopes for this bill.

If this issue is a passion, add the bill to your watchlist and speak up.

**The picture attached at the top is of the beautiful wetlands in the San Luis Valley. If you've not been, go.

https://www.watereducationcolorado.org/fresh-water-news/hundreds-of-colorado-streams-wetlands-unshielded/

https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/sb24-127