Educate yourself on greenhouse gas emissions by Ag, being open to innovation, and heat pumps don't heat as quickly.

Greenhouse gas emissions by Ag.

I got the study in my inbox from a friend. It is a study titled "Future Warming From Global Food Consumption".

We all have our own thoughts on global warming. I didn't want to rehash the entire thing today. Whatever you believe, however, if you consume food or make food, you would be wise to pay attention to things like this.

The reason I say that is that when the climate change crowd gets bored with transportation and utilities, when they work through other things, they will eventually get around to agriculture. Having some familiarity with what they think and how they see it will be to your benefit. That starts with looking at reports like the one linked first below.

I will leave it to you to read the report, but I can give you some excerpts and highlights.

--First off, what is this study about? The authors took a variety of climate models and teased out the climate implications of human activities related to food consumption and production. They then evaluated those impacts under a variety of scenarios.**

For more context on these scenarios, see the second link below. As an example, the "Regional Rivalry" scenario you'll see over and over is (quoting from the second link):

SSP 3: Regional rivalry - A rocky road

This future poses high challenges to mitigation and high challenges to adaptation

Population growth continues with high growth in developing countries

Emphasis on national issues due to regional conflicts and nationalism

Economical development is slow and fossil fuel dependent

Weak global institutions and little international trade

--Since consumption drives production and vice versa, you cannot have a discussion of Ag and greenhouse gases simply from the standpoint of what producers do. You must necessarily include consumption in the discussion.

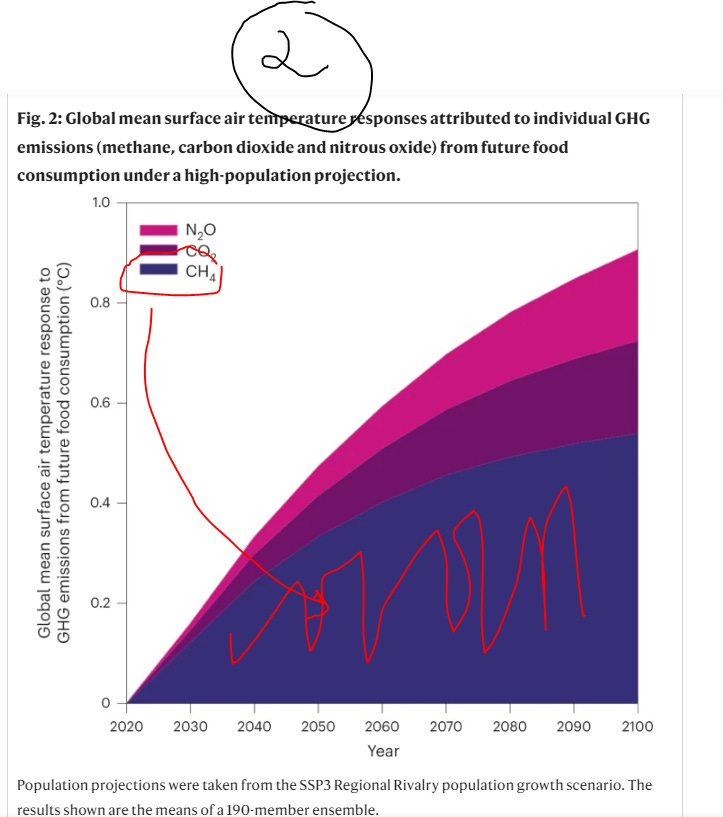

--In a corollary to the above (and in a sense or more than just food production/consumption), population dynamics will also be driving the discussion and policy. More people means more food of any kind. You get a sense of this in screenshot 1 attached. It lists out the predicted global temperature increase vs. year for the various population scenarios listed. One curiosity I noted here was how closely they tracked each other in the near term. I wonder what exactly drives such a wide disparity in predictions from 2050 on. Some kind of breeding restrictions? Another trend? More people = more climate change predicted.

--Screenshot 2 is particularly important for Ag producers. Methane (highlighted with red scribbles to make it easy) is a much more powerful greenhouse gas. I.e. it's able to much better reflect heat waves back to earth and keep heat in. Methane is also the main greenhouse gas produced by Ag (not counting the transportation to get product to market). To quote the study:

"Carbon dioxide, a gas that can last for hundreds of years in the atmosphere, is emitted throughout the food supply chain from sources such as energy use from cultivation machinery and product transportation. Methane, a gas able to trap more than 100 times more heat than CO2 for equal mass but with an atmospheric lifetime of around a decade1, is emitted primarily from the production of animal products and rice, through enteric fermentation, manure management and rice paddy methanogenesis."

I.e. methane is a more powerful gas, but it's doesn't stick around as long.

If we have more people, as is assumed for this graph, we'll have a lot more methane from making food.

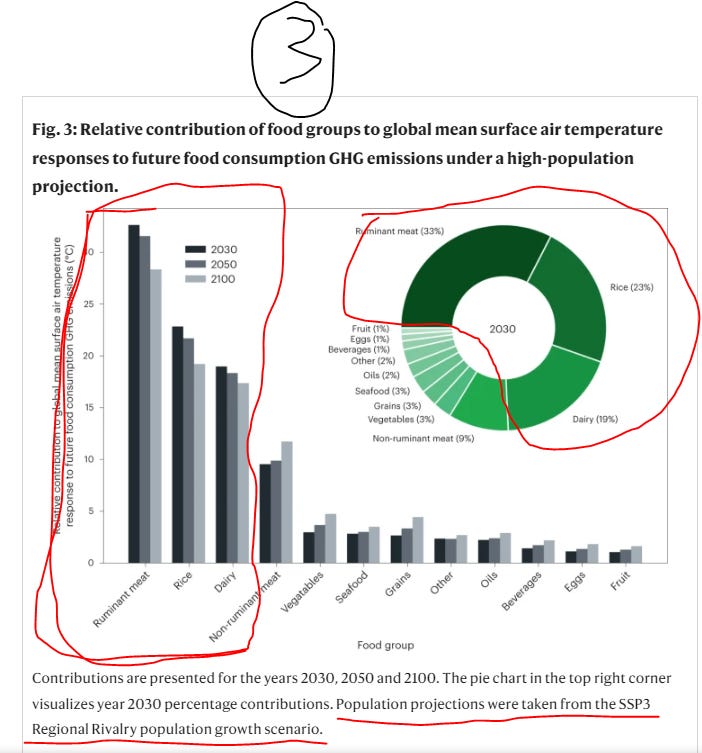

--Screenshot 3 stuck out because I had no idea that rice was such a big driver of methane producer. I knew animal production would be (both for meat and dairy), but not rice. It's a quarter of the greenhouse gas production for the globe.

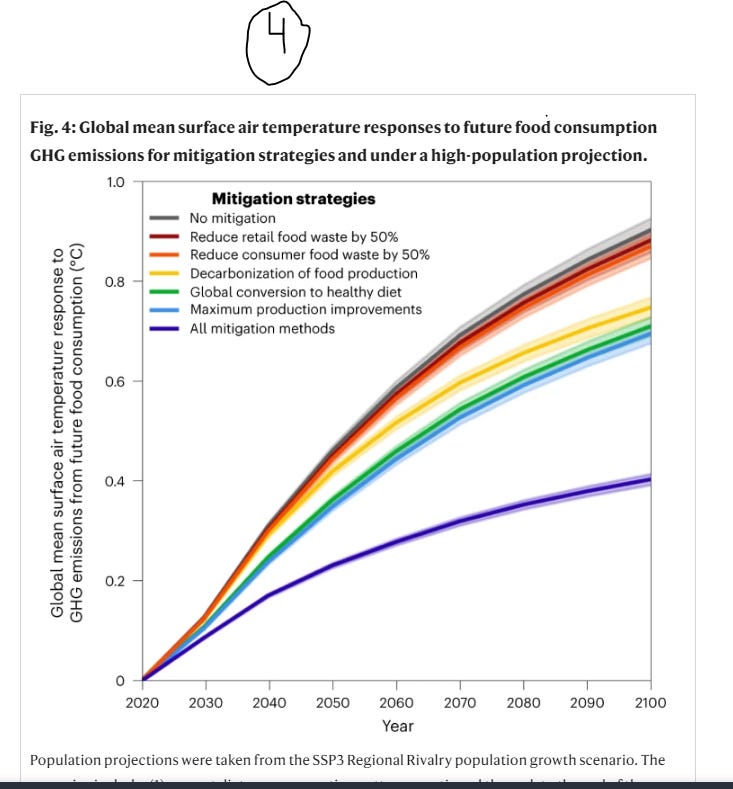

--Screenshot 4 gives the study authors' breakdown of food production and consumption's contribution to global temperature increase for a variety of mitigation strategies. Clearly they assume that doing everything on their list will have the biggest impact while reducing food waste will have little impact. Note, similar to before, that the divergence in results happens here in the short, short term (2030).

--Last point I want to make here. I want to highlight that, regardless of you feelings about the scale and nature of climate change, there are things we can do to mitigate the amount of gases given off by food production. We humans are quite good at adaptation and technology when we want to be. The thing is, wanting to be requires a spirit of cooperation.

So far, I haven't seen a lot of cooperation and willingness to be open to other views on the best way forward from Colorado policymakers when it comes to things like utilities, transportation, and how much we clamp down on Coloradans.

If that pattern holds for when they eventually get around to Ag, I don't expect much difference and a fair bit of conflict.

**I can't help but sneak in a word about modeling here. I am a decided skeptic about climate models. Here is what I will say about the validity of the study author's modeling based on experience with models in general. I.e. you can hold this to be true about models regardless of what they predict. Models are likely more accurate in the near term than the far. For this study, that means 10 years in the future vs. 30 vs. 40. Models also give a much better sense of a trend rather than specific predictions. E.g. you can't guarantee a 6.2% increase, but it's likely you'll have a small increase as opposed to a big one, or a decrease.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-023-01605-8

https://climatescenarios.org/primer/socioeconomic-development/

***Related

I wanted to include the below from The FencePost as a bit of counterpoint to the study.

I think a fair point to make is made at the end of this article:

"Mitloehner said the most important takeaway for livestock producers from climate studies is confidence in U.S. producers leading the world in efficient livestock production. The majority of the land used for beef and dairy production in the U.S. is marginal and unsuitable for crop production, making the best use of those marginal lands. Additionally, he said cattle make use of food waste from other production as part of their ration that is eventually upcycled into high-quality protein by beef and dairy cows alike. Upcycling, he said, is possible through ruminant animals grazing and eating cellulose, a substance not digestible by other species, including humans, and converting it into food with high nutritional values for humans. 'There’s nobody else who produces as efficiently as we do,' he said."

I alluded to this at the end of the post above. It ties in with my belief that one general step we should take re. climate change is to help the developing world skip ahead to our cleaner methods of food production, transportation, and energy production instead of clamping down on us while they belch out carbon.

Good luck convincing Colorado policymakers of this, however.

And speaking about being open to innovation ...

I wrote in the post just prior to this one about a spirit of openness to cooperation and other ideas and I present the interview below in that same spirit.

It's about a potential improvement to lithium ion batteries making them smaller and lighter than before. If it scales up and is economically feasible, this could have major implications for all the devices in our lives.

I present this an example of the kinds of step-wise, thoughtful sort of thing we should be focusing on.

We should encourage innovation that improves things we know to be feasible and that work now.

We should be taking small steps into the future and letting the market (a giant decision engine) decide what is working and what isn't.

We shouldn't be panicking and forcing change into one narrow area that some people think will be our savior. After all, how many times in the past has the latest and greatest not been the best? How many false starts and abandoned miracles have you seen in your life?

https://koacolorado.iheart.com/featured/ross-kaminsky/content/2023-03-10-dr-larry-curtiss-on-new-developments-in-battery-technology/

The power delivered by your home heating system.

I got the article linked below from a reader and wanted to share. It treads on pretty familiar ground, but it did bring up an important aspect of electric home heating (specifically from heat pumps) that is something I've not discussed before.

You can see what I mean if you look at screenshot 1 from the article. All other things being equal, heat pumps take longer to heat a space than combustion heating.

The reason has everything to do with the rate at which temperatures change and the rate at which heat energy is delivered. Let's back up a bit and do some fundamental physics to help us understand this better.

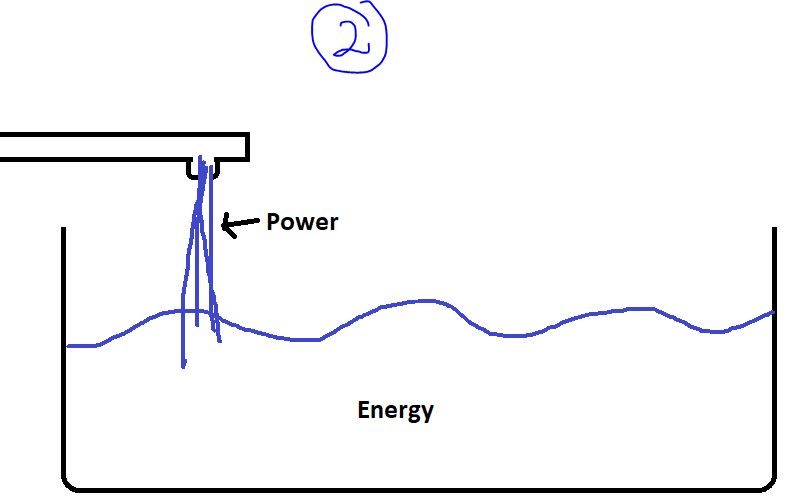

I recycled an earlier diagram from a previous post to help remind you of the difference between power and energy. Energy is an amount and power is a rate of energy flow into (or out of) a system. To use the bathtub analogy again, illustrated by screenshot 2, if a bathtub was your "system" the energy content would be the total water in the tub at any given time and the power would be the rate at which the tap is adding water to the tub.

Second, you need to understand that the rate of heat flow into an object depends on the temperature difference between that object and its surroundings. For example, if you take two chunks of steel both heated to red hot, heat will flow out of the steel faster into a bucket of cold water than it would into a bucket of boiling water because the cold water has a larger temperature difference to red hot steel than does boiling water. As another example, an 1100 W microwave and a 1500 W microwave can both bring your microwave burrito to tongue-scorching perfection, but the more powerful 1500 W microwave does it faster.

Okay. Back to the heat pumps. As was hinted at in the article snippet from the first screenshot, heat pumps can take longer to heat a room (all other things being equal) because they deliver hot air at a much lower temperature than does a furnace.

For the following, I relied on my dad (a mechanical engineer) for some numbers and I'm grateful to him.

It is common in heating systems to design them to deliver air at about 90 degrees from a furnace or boiler because anything less will feel cold to humans. That is, you can indeed heat a 65 degree room with 75 degree air, but you'll feel cold the whole time you do it and it will take longer.

The reason is the simple physics above. You can get heat to move between two bodies anytime there is a temperature differential, but the power of the air, the speed at which the heat moves, will go as the difference in temperature and 90 degree air is "faster" than 75 degree air.

Said another a furnace has more power than some of the older heat pumps. They will heat your home faster and make you more comfortable while doing it.

So what about more modern units that are coming out now? Some more exotic (and expensive) heat pumps are coming out that can deliver warmer air regardless of the outside temp and thus heat your home faster and keep you more comfortable. There are multiple ways to do this: supplemental heat (a toaster coil) and hot gas recirculation (see my earlier posts) are two ways that come to mind.

The thing is, if you are going to deliver more heat in the same amount of time, that heat needs to be sourced from somewhere. If the air doesn't have it, guess where it comes from? The grid.

Learn and remember the basic physics when you hear about the new wonder technologies that promise to let us live without fossil fuels AND no sacrifices in any other area.

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/money/consumer-affairs/how-much-buy-heat-pump-cost-install-save-money-green-tech/