A tone deaf media op ed: pointing out the log in your neighbor's eye and ignoring the log in your own. When you see the timeline, you'll know why the Closed Basin Project went South.

Only if I disagree is news coverage partisan, only if it doesn't come from "official" journalists is it not news.

The Columbia Journalism Review essay below caught my eye. I wanted to share because there are some themes which I see in a lot of writing about news that I thought would be good to share.

The essence of the article deals with a news outlet that popped up in Wyoming that is seems to be a Republican/conservative mouthpiece. This comes amid the (quoting) "waning" of competing local news outlets. It also is characterized by the writers as pushing "climate misinformation" and "anti-trans talking points".

I don't take it as my job here to defend the new paper. I will not wade in on the issue of whether what they write is misinformation as opposed to a difference of opinion. I will not wade in on whether what they write is, again, a difference of views or anti-trans. I do not know enough about the papers mentioned to comment either way about any of the allegations.

What I want to focus in here is, I think, a certain bit of hypocrisy and tone-deafness among some in the media.

Reading the essay you'll come across things like (quoting):

"Removing material without explanation contravenes the Society of Professional Journalists’ (SPJ) ethical code around accountability and transparency."

"He [Mike Yin, a Democratic member of the Wyoming House of Representatives] added that it fit a pattern of sensationalist, clickbait coverage from the newsroom. The decline of local media has 'left that opening,' which has led to 'Cowboy State Daily [the news outlet in question] filling a void very quickly,' Yin told me. 'Surprisingly quickly.'”

"Amid concerns of partisan agendas seeping into local news, the Tow Center looked at the outlet’s coverage of two hot-button culture war topics: the climate crisis and trans rights."

"Where is all this heading? There are concerns declining standards of local journalism will have implications for the health of democracy. 'You can see it time and time again around the globe, and certainly here in the US, that less savory information is going to flood in to fill that vacuum,' Copeland said, making it 'difficult for folks to participate in civic life in a fully informed way.' When WyoFile was founded, in 2009, it arrived as an outlet dedicated to enterprise reporting that topped up the important daily news of Wyoming’s legacy papers. Back then, 'we were maybe providing the protein to the carbs and dessert” of other media offerings, Copeland said. Today, 'we’re the protein and the leafy greens and the whole grains—and increasingly the rest of the landscape is doing more of [just] the dessert.' In this sense, Wyoming’s experience—declining local news, a vacuum of good information, a mega-rich partisan setting up a news outlet that has pushed anti-trans views and climate misinformation—is an alarm bell for the rest of America. If local news cannot find a route to sustainability, actors with cash and questionable motives are free to inject their talking points into the political bloodstream. It’s a warning for where we’re heading as news deserts take hold."

"But the outlet’s green-energy-skeptic stories have helped encourage a hostile environment for people trying to transition to a lower-carbon economy, Tennessee Watson, state desk editor at WyoFile [a nonprofit paper and, from the context of the article, likely an ideological South Pole to the other's North], told me. 'The anti-climate-change reporting feeds into a certain narrative' that makes it harder for political candidates pushing to decarbonize to gain traction, she said."

As I read these, I have the image in my mind of someone eating fried chicken and then criticizing me for eating chicken. Outside of conceding a few points such as the need for the Wyoming paper to be transparent about funding (a comment I would also make about nonprofit news orgs), you'll pardon me if I don't find the criticisms above to be particularly damning of this one outlet.

How many stealth edits at liberal news outlets do you hear about in conservative news outlets?

How many times have liberal news outlets been partisan in their agenda and in what they choose to cover vs. not cover?

How many times have reporters placed themselves alone on the bridge defending Democracy all the while pushing their perspective and agendas? That is to say, is a conservative outlet pushing their perspective any better or worse than a liberal outlet like the Sun or CPR pushing theirs?

And the last quote above is especially telling. I'm sorry, but is it the job of a media outlet to help politicians push their policy agenda? An agenda based on things we might not see eye to eye on?

It's staggering to me sometimes how reporters can be so incredibly oblivious.

Fortunately, none of this leaves you and I, the consumers of media, in a different spot than we were at any other point. We get to control what we consume, what we let into our brains.

Be smart about what you consume. Eat a balanced diet, pulling stories from multiple sources and perspectives. Know who funds what. Follow back to original sources. And, if you see a story on social media, take 5 minutes to Google it to see what other links and stories there are.

https://www.cjr.org/tow_center/wyoming-local-news.php

Related:

A few things in brief that struck me after writing the above. Good things to remember, consider it a glossary/guide of sorts.

--"Non-partisan" in the media does not mean unbiased or neutral. More often than not, I've found it to likely refer to its literal sense: that the organization is not affiliated with a major political party.

--Experts quoted in articles are also not unbiased or neutral. To be sure this is the case when the experts are from a social science or humanities field. To understand what I mean, dig back in the stacks of my posts and see the one about the ideological leanings and political contributions of university professors.

--Nonprofit news organizations are not a priori better, more balanced, or more trustworthy than any other. They are merely funded differently (and do your due diligence to see who it is that funds them).

--Journalists often use style guides and recommendations as to nomenclature and names to give to things. Note that these guides are also not any more ideologically neutral or morally superior in their conception, characterization, or connotation than any other colloquial expression. It's merely a convention that a group of journalists agreed on.

I said in an earlier post that the Closed Basin Project was a clever idea that soured like old milk.

I didn't just mean that in an entirely literary sense. I chose that simile because it is analogous to what happened. The Closed Basin Project started as (debatably) a clever idea that, because it sat too long, became a problem.

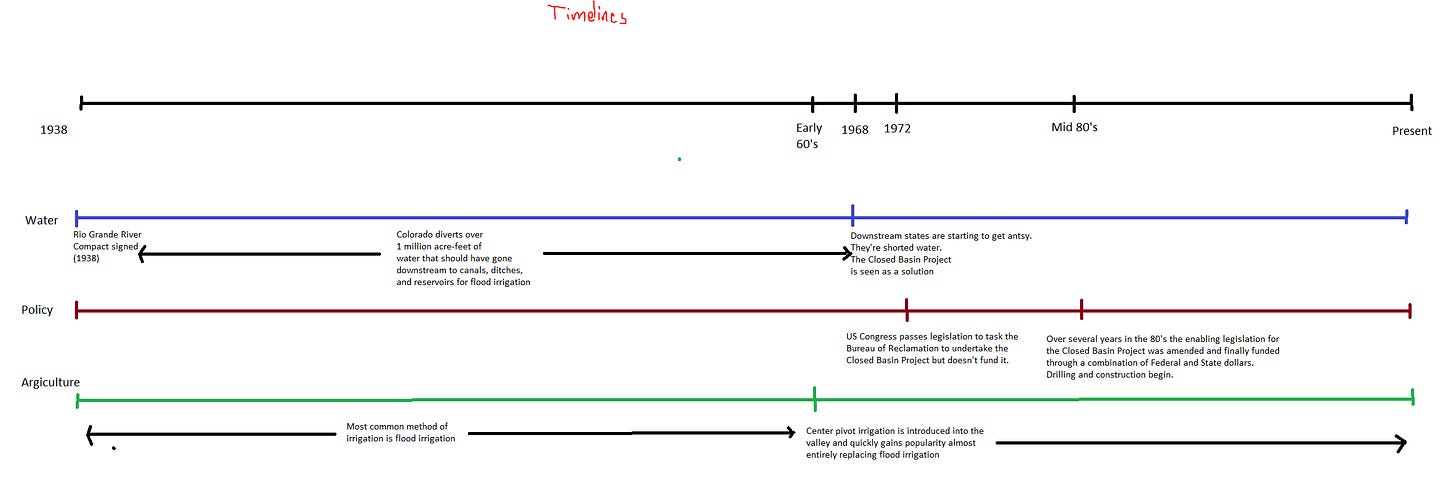

This is the next installment on the Closed Basin Project in the San Luis Valley and today I want to drift away from what basins are and why there was "salvage" water in the San Luis Valley to make good on Colorado's part of the Rio Grande Compact to talk about how things happened in time.

Knowing the time, policy, and agricultural dynamics help tell the story of how things went wrong.

Take a look at the timeline I made and attached. It shows 3 parallel tracks: water, policy, and ag. Times run vertically down. Where things are not really well-defined (or are, as in the case of enabling legislation for the Closed Basin Project, on short enough times to make things too "busy" in the picture), I've given rough dates. Also, this is not to scale.

I want you to note the interval between the initial enabling legislation for the Project and the start of drilling. Quite a bit of time.

Now look below to note the simultaneous developments in agriculture, focused here on irrigation methods.

I covered what central pivot and flood irrigation were in a previous post but re-attached pictures 1 and 2 from a previous post in case you missed it.

What is not apparent from the photos are two critical differences between the two.

Flood irrigation is time- and labor-intensive. If you've not ever watched it, it's quite a process. After filling a ditch, you go pipe by pipe, row by row, adding water to each of the tubes and using them to siphon water out of your ditch and into the rows.

With central pivot, once the equipment is set up, you literally push a button. That's it.

Additionally, central pivot irrigation is much much more efficient. To get enough water (using made-up round numbers) to grow a crop might take 150 gallons by flood irrigation and 100 by center pivot.**

Let's put all the pieces together:

--The closed basin has "salvage" water in it that could be used to meet Colorado's compact obligations to its downstream neighbors.

--The closed basin has this "extra" water because farmers used flood irrigation which has a lot of run off to soak into the ground, and because the state was willing, per the engineering report linked first below (see the discussion starting on the bottom of page 18), to tolerate drying the land out some--while lowering the water table--to meet its compact obligations. They thought it wouldn't have the risk of harming anyone and this was done at a time when man was a lot more willing to tinker with nature, thinking he could bend things to his will without consequence.

--The Feds and Colorado decide to tap this reservoir, put it in a canal and let it flow to the river. Between the deciding and the doing were years and years.

--Meanwhile, farmers are busily (and quickly) switching to center pivot irrigation for ease and efficiency.

--Center pivot irrigation has less run off and thus is not refreshing the closed basin as much as the older, flooding method of irrigation.

Do you see where we're heading?

Old metal bridges were so over-designed that the workers could easily miss a few rivets in the joints between plates and girders with no ill effect: the loss was overwhelmed by a surplus.

A similar dynamic happened in the closed basin. With a switch of irrigation methods and enough time, a good idea based on a surplus of water was ruined by a lack of input. Less water was coming in but, in the grand tradition of a government program, no one stopped to ask whether this meant the project should stop or be reconsidered.

Less water in and more coming out in a bathtub means the water level will drop. The same has been happening (WITH AN IMPORTANT CAVEAT TO NOTE IN FUTURE POSTS--BE WATCHING) in the closed basin. Take a look at pictures 3 and 4 attached. They come from the PowerPoint linked second below and show the water levels in the unconfined aquifer of the closed basin. 3 is a graph and 4 is a contour map, but remember that the contours show the water levels below the average and not the physical contours of the earth at the surface. This contour is overlaid on top of a map that should be familiar from the last post, it shows the wells of the Closed Basin project.

There is one last dynamic I want to mention here before wrapping this installment.

Underground water can be tricky. Sitting right next to minerals all the time it tends to dissolve things. Those dissolved solids (salts and other naturally-occurring chemicals) make it a little different than surface run off.

You have to be careful in using underground water to recharge a river because the balance of chemicals can alter the river's chemistry and make it unsuitable to the creatures that live there or for use downstream.

it was therefore important for the Closed Basin Project to consider the salinity and other dissolved solids of the water it pulled up out of the closed basin. That was investigated (see the engineering report linked first below bottom of p 21 to top of 22), and it was felt that if the wells needed "sweetening" with other water, this could be accomplished by adding surface runoff to the canal linking the wells to the Rio Grande or mixing water from wells with different levels of dissolved solids.

The next installment will look at other dynamics at play in the closed basin and approach it from a different perspective. In particular, I want to examine the idea that the Closed Basin Project isn't the sole source of the woes of farmers in the San Luis Valley, and I want to go over a reminder that one way or another, compacts will be met.

**The ease and efficiency extends beyond just making farmer's lives easier. It enables them to wring more out of their farms. I was told a story of farmers formerly getting two cuttings' worth of alfalfa under old irrigation methods going to three cuttings worth (i.e. more product to sell in a given year) with center pivot because more water could be turned into crop with less wasted as runoff. More on this later.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Nz-tMUYB6FBU5rH7FeXvmgbWUqhY1VwN/view

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1I4-LlKlA3T7z71j50qBN_x4dQEO3YltZ/view?usp=sharing