A three-parter on flood irrigation today: the process, the physics, and some scattered observations about water rights on the Eastern Plains.

Flood irrigation: the process.

A friend of mine who farms offered me the chance to come out to help/observe when he did flood irrigation on the corners of his field. I took the offer and thought I'd share some random things I learned while doing so. I'll be dipping back into some water news over the next few days so I thought this would make a good (and interesting) introduction.

Note that the pictures I am posting here are not from this man's farm (nor will I share his name) because I didn't ask him permission to do so. The images you'll see are representative, but they're from the internet.

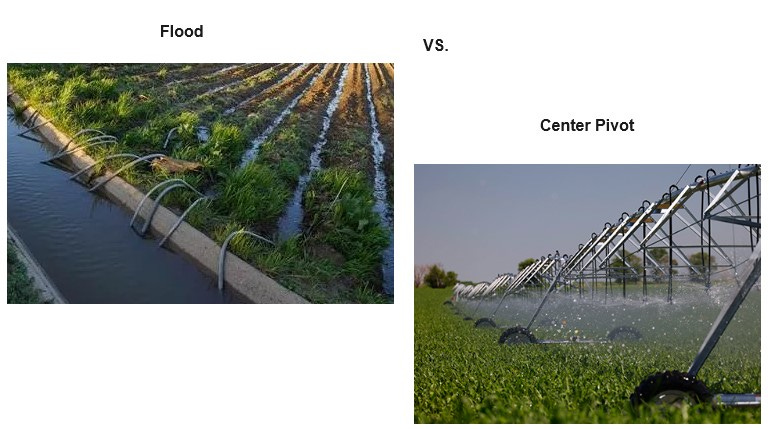

When I say flood irrigation, what I mean is what you saw in the picture at the top of the post, the one where you literally flood the furrows from either a ditch running alongside the field or from a hose running alongside it. This is as opposed to center pivot irrigation where a sprinkler moves around the field in either a partial or complete circular arc.

Most fields, especially older fields, are not circular and so there is always some leftover bit of land that a center pivot sprinkler cannot irrigate. This always leaves the farmer with a problem to solve: it would be nice to use that land to grow things to sell, but how to irrigate it?

In the case of my friend, since his field pre-dates center pivot irrigation, he already had a lot of the infrastructure in place to use flood irrigation (in fact, the entire field prior to the 70's was flood irrigation). This means that his field had been graded and was surrounded on the perimeter with a ditch which connects to his irrigation canal. For him the solution is then pretty straightforward if not necessarily easy: use flood irrigation for the "corners" and center pivot in the middle.

I'll cover the process of doing flood irrigation in the posts today, but let me pause here to share what I learned of it. One, it's not easy. Ditches have to be maintained (God save the original farmer who had to dig them because I'm betting it was largely hand work and this is a big series of fields). Two, as I'll show you in the second post, this is not just a matter of "stick a pipe in a ditch and water comes out". That is, as is always the case in Ag, there are levels of complexity here that you cannot appreciate until you actually do these things.

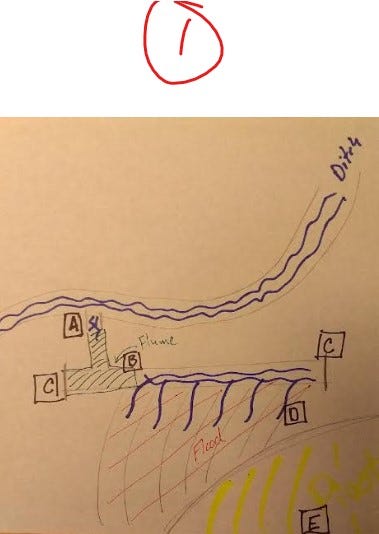

To help you get a sense of how things relate in space on my friend's farm, I attached a crude hand drawing as picture 1 which gives a bird's eye view of the layout.

My friend still farms his family's land (settled back before this was a state), and the original irrigation system was a series of canals coming off the Platte River. A headgate connects his field ditches to this canal. That is A in the drawing.

The only reason he has a headgate, the only reason he can get water from this ditch at all is because he maintains a membership in something called a "ditch company". It's a nonprofit that pays a membership to be a part of and this entitles him to draw water out of the ditch. His dues also pay for the upkeep of the canal. If you want more context, check the link at bottom.

Back to the headgate. When he opens it, water from the canal flows through a weir (this is B -- more later) and then can divert either to the left or to the right.

The part of land that my friend was irrigating was on the right as you face the canal, so he had blocked off (with boards and a piece of canvas) the lefthand outlet of the weir (C in the drawing) and then had also blocked off his own ditch about 300 yards or so away down the right side from the weir (also C but on the right). The ditch continues past that point (remember it circles the whole field), but there's no point keeping it open past there as beyond that region the center pivot can water.

So, canal water flows in to my friend's ditch and begins to fill it. This ditch is higher than the field in elevation and so a series of curved aluminum tubes (about 3 or 4 inches in diameter) allows water to flow out of his ditch and into the corner of his field. This is D in the drawing.

This "corner" of the field (the part that gets water from the center pivot sprinkler is shown in the drawing as E) is then literally flooded with water to give the corn plants there a drink.

You must remember that this is not a static system. That is, water is flowing the entire time: out of the canal, into his ditch, down the tubes and into the field. We're not filling ditches to store water, we are carefully managing where water flows out of the canal. We are directing it to various parts of the field.

As such you have to be careful about setting up and moving the tubes. You have to get them flowing as the ditch nears the top and you can't just randomly stop them once you start. Doing so would make the ditch overflow.

Still, a goodly portion of time in flood irrigation is spent in waiting. Waiting for the ditch to get high enough to do the first set of tubes. Waiting for the furrow to fill. Then moving the tubes in a set pattern (again, you can't move all of them at once, you take a few at a time to maintain the outflow of water from your ditch) to the next bit of land. And repeat.

I should amend that actually. It's waiting punctuated by labor. Physical work in the out of doors, sometimes in brutally high temps. I was fortunate enough to have done this in the morning on a coolish day. My friend was telling me about sweating it out doing this on a really hot day a couple weeks prior.

Flood irrigation is also a fair bit of labor at the start of the season. Maintaining your own ditches is a lot of work, albeit helped by machine. There is, unforunately, no machine to unblock the ends of the furrows. You do that by hand with a shovel prior to your first flood irrigation of the season.

I was glad I went. I'm also glad I don't do it for a living.

In post two, I'll look at a little of the technical detail and technology of flood irrigation.

Flood irrigation: the technical detail.

There are some interesting technical and physics aspects of flood irrigation that I wanted to share.

First, you have to be aware that my friend is not entitled to as much water as he would like, nor at any time he would like. In the post above, I mentioned that his land had shares in the local ditch company. This entitles him to have water, yes, but only in proportion to how much of a share in the ditch he has.

Long story short, he has to measure out how much he's using and not exceed it. How though? I mean, he's not dipping water out of the ditch by the bucket and dumping it on his fields.

Water flow, thus quantity, can be measured in a number of ways (see the link below --note it's from a company selling something, but this was the least technical reference I could find to share so there we are), including some fancy electric gadgetry.

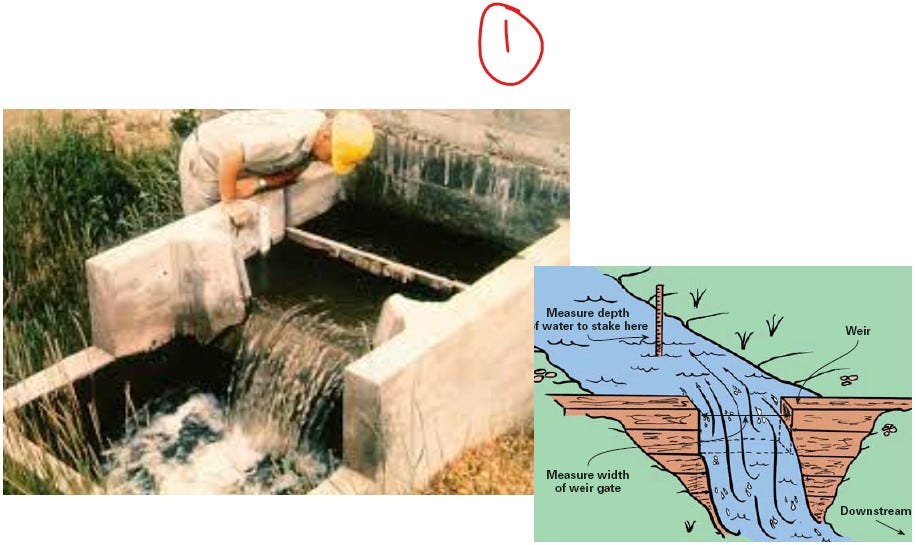

A sturdy and proven technology to do it is by using a weir. Screenshot 1 attached gives you both an actual picture and a schematic drawing.

A weir is basically a box--my friend's was concrete in roughly the shape of a T with the stem being the input from the canal and the top cross bar being the outlet to the ditches running around his fields--which channels the water into a certain shape to control the speed of the flow.*

This implicit speed and size of flow are combined with the depth (see the screenshot, that's what the man in the hardhat is doing -- he's measuring the depth with a built in ruler) and how long you run it, you can calculate the amount of water that has gone through your weir.

You don't actually do this calculation in practice. The people that designed your weir give you a table (see the link below) which you can read to the appropriate depth and get a flow rate/volume.

My friend thus adjusted how much his headgate was open, how much flow from the canal he got, in order to get the right depth needed in his weir so that he wasn't taking too much or too little water.

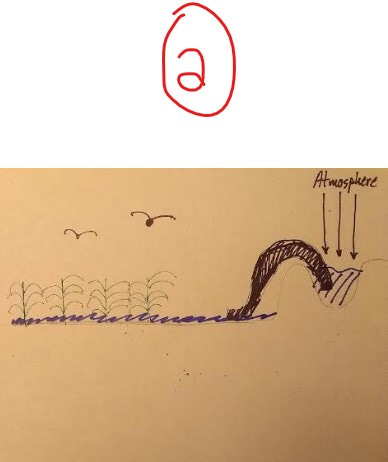

It's interesting to note that the entirety of the flood irrigation process (at least as practiced by my friend) involved no electricity. Not even any moving parts. The motive force here was the same as my earlier post on crushing a rail tanker car (see the second link below): the atmosphere.

Picture 2 is another crude hand drawn visual aid. It's a cross section of the field and the ditch so you can get a sense of the relative elevations. The ditch is on the right, the field (with corn plants and little birds) is on the left. The aluminum pipe is shown running from ditch to field.

When filled these pipes have an unbroken connection to the water in the ditch and thus act exactly like siphoning gas out of a car or sucking up that delicious soda through a straw. The ditch is open to the atmosphere on the top, so the pressure of the air on the water in the ditch (unbalanced by any similar pressure below) is enough to get the water up over the hump at the edge of the ditch where gravity takes over and lets it flow down to the field.

As long as you have air pressure, a tube that has no openings, and water in the ditch, you'll have flow. No outside power needed.

Last thing I wanted to talk over was how you get those tubes started. The short version is: it's harder than it looks!

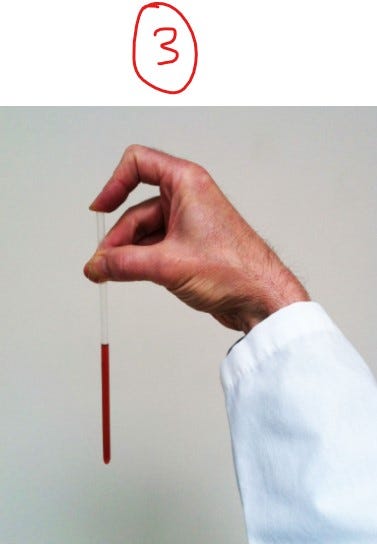

The process of starting the tubes is as I have it above. It's a function of air pressure. Check out picture 3 attached. If you dip a straw into a liquid, cap it with your finger, and pull up, some of the liquid will be stuck in the straw.

As you lift the straw up, some of the liquid will start to fall out of it. If the upper end is blocked, the liquid will only fall out of the straw until the weight of the remaining fluid is balanced by the difference in the pressure between the outside air and the little bit of air left in the straw. Break the suction and the game's off. Now atmosphere can get in behind the fluid and it will drain.

The same principle is at work in starting the aluminum irrigation tubes.** There are a couple ways to do this. One struck me as similar to a dance and it's what my friend did. Standing next to the ditch you force the free end down into the water, cover it with your hand, pull up to get some fluid in the tube like the straw, pop your hand off briefly, then quickly push back down, cover, etc. Do this enough and you'll fill the tube with water. A quick dumping motion over the side of the ditch starts the flow.

I couldn't do this to save my life. At all. I had to do the second, less glamorous method. I got down next to the ditch on hands and knees, submerged the entire tube, blocked the crop end, and quickly lifted it out and down. Same idea--you're filling it with water and not allowing it to drain--just not as elegant or as cool-looking.

In keeping with what I wrote in post 1, a big takeaway here is that if you think that Ag is simple, I urge you to look deeper into the physics of what farmers and ranchers do. Get out into a field and try it. See all of the things that you thought were mindless or easy.

You'll find surprising complexity and come away with an appreciation for the people that do this for a living.

Part 3 is scattered observations and things I learned about water rights doing this.

*Technical footnote: The speed of a column of moving fluid varies inversely with the cross sectional area of that column. That is, if you increase the cross sectional area of a fluid that's flowing, you will decrease it's speed and vice versa. This is part of the reason why partially occluding the end of a hose with your thumb makes the water squirt out: you pinch down the area of flow and the water speeds up.

**Technical footnote: remember from the previous post that these are big tubes. They're 3 to 4 inches in diameter. You cannot simply suck on them like a straw or a tube which you would use to siphon gas.

https://www.micro-hydro-power.com/how-to-measure-water-flow.htm

Flood irrigation: the scraps left over. Random thoughts/observations.

I quite enjoyed talking with my friend as we irrigated his field corners because I learned a couple interesting things about water rights that I thought I'd share.

If you would like a deeper understanding, some background/context, check out the link at bottom. It's Colorado's own page on water rights (a subject which, it seems, you could spend weeks on and still not have a full mastery of).

My friend's land has been in his family for generations, since before there was a State of Colorado in fact. I remember him joking during the exceptionally wet and cool summer of 2023 that it was probably weather like we had then which convinced his ancestors to settle here, especially given how many ways this land tries to kill (or ruin) you.

His ditch water rights date to (and have been "proven up", verified that is) to about 10 years after Colorado became a state. That means that he has quite senior water rights, which in turn means that he's near the first in the line for water off the Platte. Well ahead of most others.

He also has some center pivot wells which draw out of the acquifer underneath and supporting the Platte itself.* These wells date to about the mid 70's (the time when center pivot came on the scene), and are thus JUNIOR to his own ditch water and other users.

This struck me as strange: same land, same farm, in some ways arguably the same water, but the pivot well is older and thus subordinate to his own alternate source among others. In practice this means that when he pulls water from his wells to use his center pivot sprinklers, he must make up that water; he must "repay" what he has "taken" from downstream and other senior water users.

How?

His ditch water. He repays the loss from his younger wells but diverting some of his ditch water into a reservoir every winter. Over time, this water percolates down into the soil and, according to the state engineer, migrates to the river making up for the amount that might have migrated had he not pulled from his well.

Why winter? Two reasons. One, other farmers aren't using the ditch to irrigate. Two, it's the interval of time calculated by the state engineer to get the water into the river for next year.

One last niblet. If you're like me and have seen center pivot sprinklers on at all times of the day and all days of the week (as opposed to my own sprinklers which are on a set timer), you may have wondered at that.

My friend told me that the time and day he can run his sprinklers is somewhat constrained by what his well can provide. That is, it'd be most efficient to water early in the morning on a set schedule, but the well may not have enough water to do that. You have to water when the well has enough.**

I hope you've enjoyed reading this as much as I enjoyed learning it and then writing. If you have a topic that you'd like to share, esp if it's related to Ag, let me know.

*Stay tuned on this. when I revisit the Closed Basin Project in the San Luis Valley the idea that underground water "pushes" up on a river channel and allows water to move in that channel will be reappearing.

**Again, stay tuned. This figures into the Closed Basin Project too.

https://dwr.colorado.gov/services/water-administration/water-rights

Related:

The Killdeer, a shorebird who doesn't live at the shore.

While working with my friend I heard quite a few killdeer birds on his property (see the photo attached and the link below).

Matter of fact, and this could just be that old psychological effect where you see red cars everywhere because you're thinking of buying a red car, I'm seeing killdeer in lots of places around where I live this year.

Saw one in the yard of the cement mixer/landscape material supplier one day. Heard one (and some younguns) in the stormwater retention pond of a new building the other.

Both had some puddles of standing water which dovetails (pun intended) nicely with the nickname above: a shorebird who doesn't live at the shore.

Cute little characters aren't they? They're also the ones that feign injury if you get too close to their (ground) nest so that they can lure you away from their babies.

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Killdeer/overview